by Madeline Freeman pg 89 Big Hill Country 1977

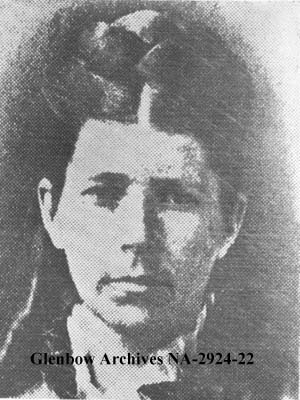

Tall prairie grasses screen a neglected cemetery plot on the Stoney Indian Reserve in the foothills of the Rockies. One of the headstones marks the grave of Miss Elizabeth Barrett, a gently-reared schoolma’am who, at the age of fifty years, ventured across the trackless plains in 1875, to take her place in Western Canadian history as a pioneer missionary teacher who was one of the signers of the famous Treaty No. 7 at Blackfoot Crossing.

Elizabeth Barrett was a teacher in Orono, Ontario. When the Rev. George McDougall stumped up and down Eastern Canada in 1874, raising money and helpers for mission outposts in the West, Miss Barrett answered the call.

She alternately shivered and sweltered in June and July of 1875, as the wagons jolted over the endless plain for five weeks of primitive travel. On arrival at Prince Albert, the party transferred to the York boats on the North Saskatchewan and made their slow passage upstream to Fort Edmonton. Here she again climbed aboard a prairie schooner. Her final stop was Whitefish Lake, the stockaded mission of the Cree missionary, Rev. Henry Steinhauer.

Elizabeth needed the white heat of missionary zeal to sustain her over that first year in the great lone land. In January of 1876, she writes:

“As regards myself, I thank God I can say by His Word and by His Grace, I am living and growing. Only for the sustaining strength of these, I think existence itself to me here would be unendurable …

“As for letters, I have never received one from Ontario since last June, nearly seven months ago. I have written again and again, and am confident that my friends have done the same, but for some reason the letters have failed to reach here . . . seven long months and not a word from home.”

Elizabeth Barrett talks about her work with the Indians in that same letter:

“My not understanding the language has been the greatest drawback to my usefulness among the people. Just think, dear Sir, for a moment, of my position. Here I am surrounded entirely by Crees, speaking Cree always among themselves, almost without exception. I find the Indians’ hearts cannot be reached except through their own language. Kindness will win their favour and esteem… but their hearts … no, not till you approach that citadel through the avenue of their own language can you find entrance.’

Fellow missionaries subsequently reported that Elizabeth won the Indian’s love as she broke through the language barrier. Her homesickness gave way to enthusiasm. When Rev. Steinhauer despaired of raising enough money for a desperately-needed new church, Miss Barrett contributed the princely sum of one hundred dollars from her meagre earnings.

She lived in a rough frame building with a clay floor and windows made from stretch-dried hides. When the hunters were unsuccessful in bitter weather, the precarious food supply dwindled to nothing but pemmican, rabbits, fish, even incubating eggs.

The plucky teacher stifled her loneliness as she fought physical cold and monotony but she couldn’t overcome her longing for the refinements of the life she had left behind. On receiving some magazines she writes:

“But to me here now, in this lone land, there was a deeper interest attached to them (the magazines) than ever before. I confess that never had pictures such charm for me as I now find in gazing on the many lovely forms and faces in those illustrated papers we received last month. It seems to bring me back again into refined and cultivated life, at least for the moment.”

Elizabeth Barrett left Whitefish Lake early in 1877 to join the Rev. John McDougall and his family at Morleyville in the foothills of the Rockies. Once again she faced the hardships of prairie travel before the days of roads and bridges. Travelling south to Fort Edmonton and then taking the Blackfoot Indian Trail, the party made camp each night in coulees that would give them shelter from the bitter winds of the prairie winter.

At the new mission, Miss Barrett coped with a new language, that of the Stoney Indians. She again experienced the hardships and discomforts of a frontier mission. But she was now tougher in body and spirit, and, working with the magnetic John McDougall she experienced the challenge of those earliest days in southern Alberta.

The last great historical pageant of the West was held at Blackfoot Crossing in September of 1877, and a full party from Morleyville made the long trip for the occasion. The Rev. John McDougall was anxious that his Stoney Indians be given equal treatment with their natural enemies, the powerful Blackfoot when Treaty No. 7 was signed between the Government of Canada and the Indians of the southwest prairies.

Rev. McDougall pitched his camp on the north side of the Bow River with the Stoney and Cree encampments. From her tent, Miss Barrett looked across to the orderly tents of the Mounted Police and the white tents of the Treaty Commission, pitched on the south side. Hundreds upon hundreds of Blackfoot lodges spread through the valley, and the preparation of meat, tanning of hides, the singing and the feasting went on, uninterrupted. On the hillsides, 15,000 or more horses of the Blackfoot grazed untethered. The fully-armed Indians were resplendent in smoke-tanned war shirts trimmed with ermine or fringes of otter and fox. Intricate beadwork adorned their moccasins and headdresses. Thick shields of buffalo hide were as gaily painted as their teepees in the valley. If trouble erupted here, the Blackfoot Confederacy had all the advantages.

But the one hundred and eight officers and men of the Mounted Police were accepted as representatives of the Great White Mother’s authority. The signing of the treaty took several days and Elizabeth Barrett took her place in Western history when she signed her name to the document as one of the official witnesses.

In 1878, John McDougall sent Miss Barrett to Fort Macleod to open a Methodist Mission and School. Accompanied by Gussie McDougall, daughter of the Rev. John’s first wife, she forded challenging rivers such as the Ghost, slithered in the mire and slept on grass saturated with rain as they travelled the open prairies to her new post. Unprepared for the lusty life of the Fort, she looked askance at the thirsty freight cadgers and gamblers who rolled through the swinging doors of the saloons. But she concentrated on the business at hand, and it is recorded that the children of the famous scout, Jerry Potts, were among those on her school register.

Miss Barrett continued teaching at Macleod and then again at Morleyville until 1885 when she returned to Ontario for a well-earned furlough. She could not be persuaded to remain in the East and she returned to the mission in the shadow of the Rockies where she gave two more years of devoted service. When she became ill she was nursed by the McDougall family and died at their home on February 7, 1888.

There is peace in the cemetery overlooking the old church at Morley, but the brown-eyed susans and tall grasses have started to encroach on the old headstones.

Elizabeth Barrett was one who treasured the elegancies and refinements of life as she wrestled with this raw, new land.

NOTE: Mrs. Pat (Madeline) Freeman of Toronto, Ontario, is a great-great niece of Elizabeth Barrett.

Barrett’s death is listed in the article as 1893 and by her relative, the author as 1888.

Thank you.