by Jack Fuller – pg 330 Big Hill Country

DP was a quiet man. Almost shy. Perhaps a little awed by the women in his life for he was, first and last, a horse and cowman of the old school. Soft-spoken with a subtle sense of humour and, a soft, almost silent laugh. In a country where cussing was a fine art his sole contribution to blasphemy was, “Great Scott, is zat so.” Once when told that the Mounted Police had found fifty of his beef hides cached in the Red Deer River his only comment was, “Great Scott, I wonder who did it.” (The rustlers were later caught and drew seven years for luck.) Though a canny Scot by birth, he was, in many ways, generous to a fault. He may not have always paid top wages but his monthly grub bill must have been the highest, for his hospitality was the warmest in the country. Kids, cowpunchers, cattle buyers, horse thieves and Indians rode miles out of their way to rest their elbows on Momma DP’s red flowered tablecloths and she served more between-meal dinners than any short order cook in the country. Looking back across the years, the untiring effort, energy and achievements of such Old Timers is almost unbelievable; few could wear their moccasins today.

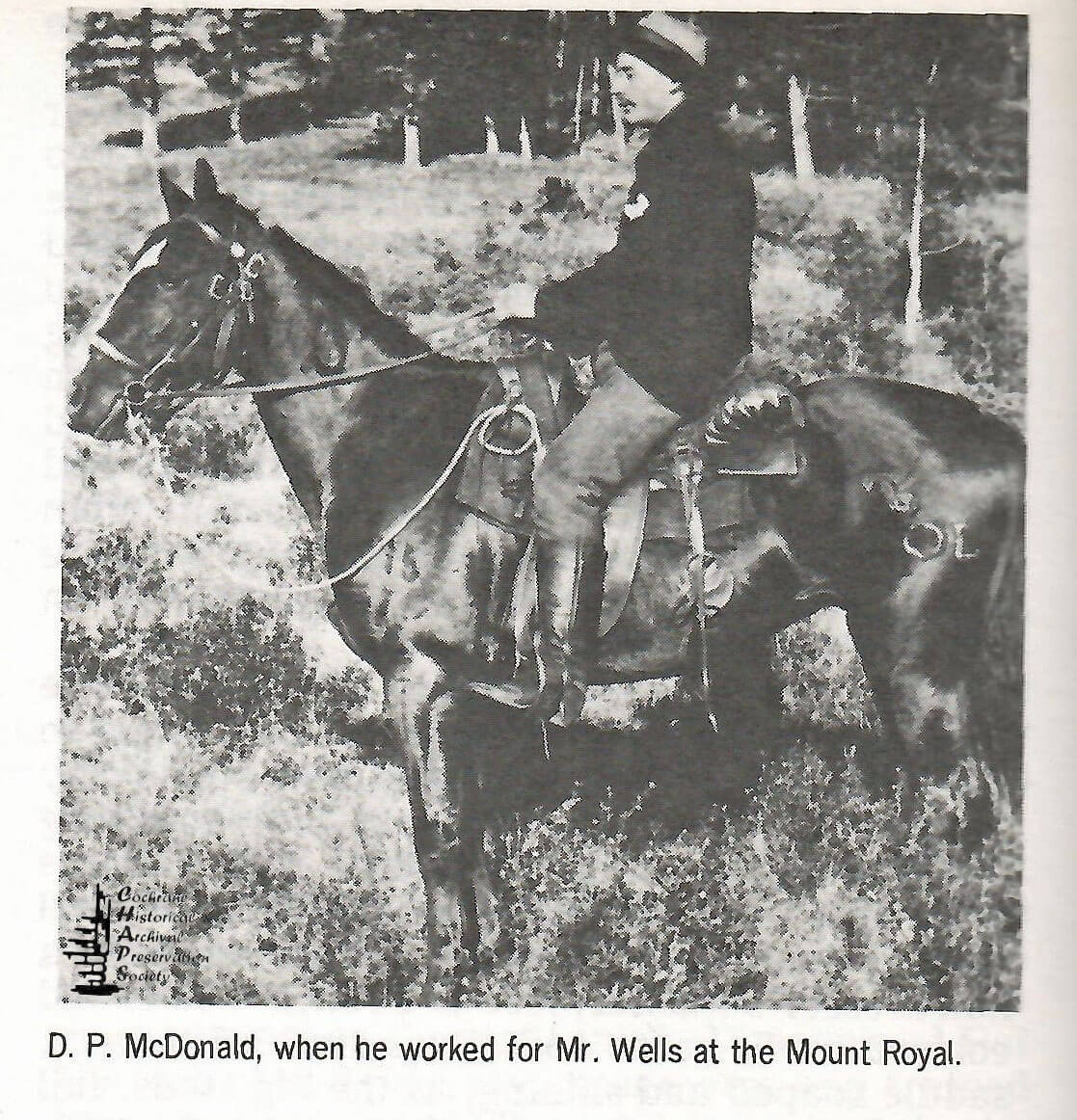

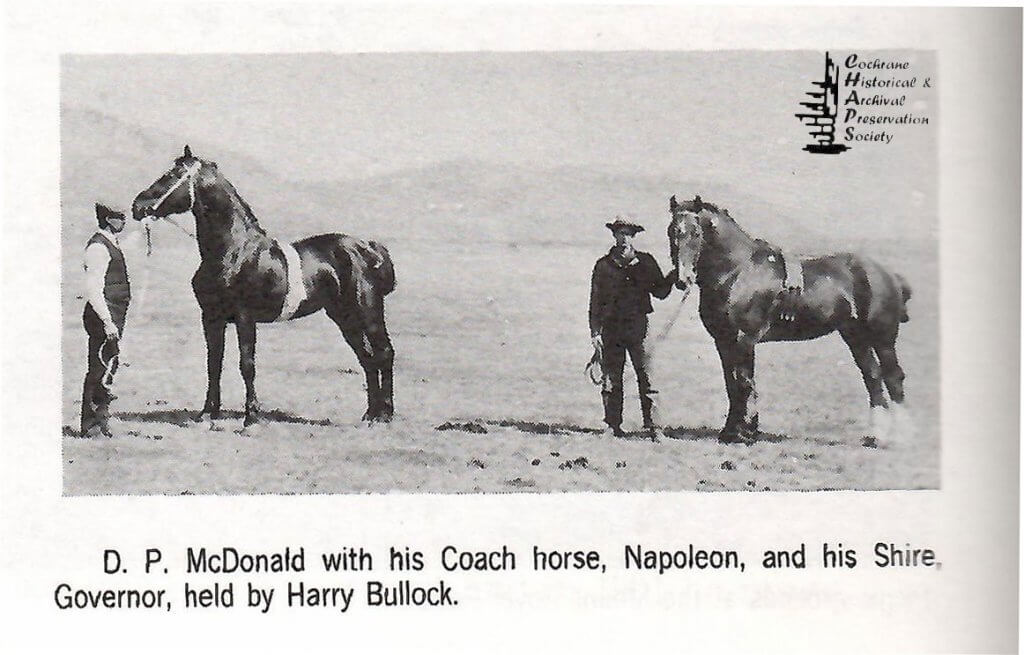

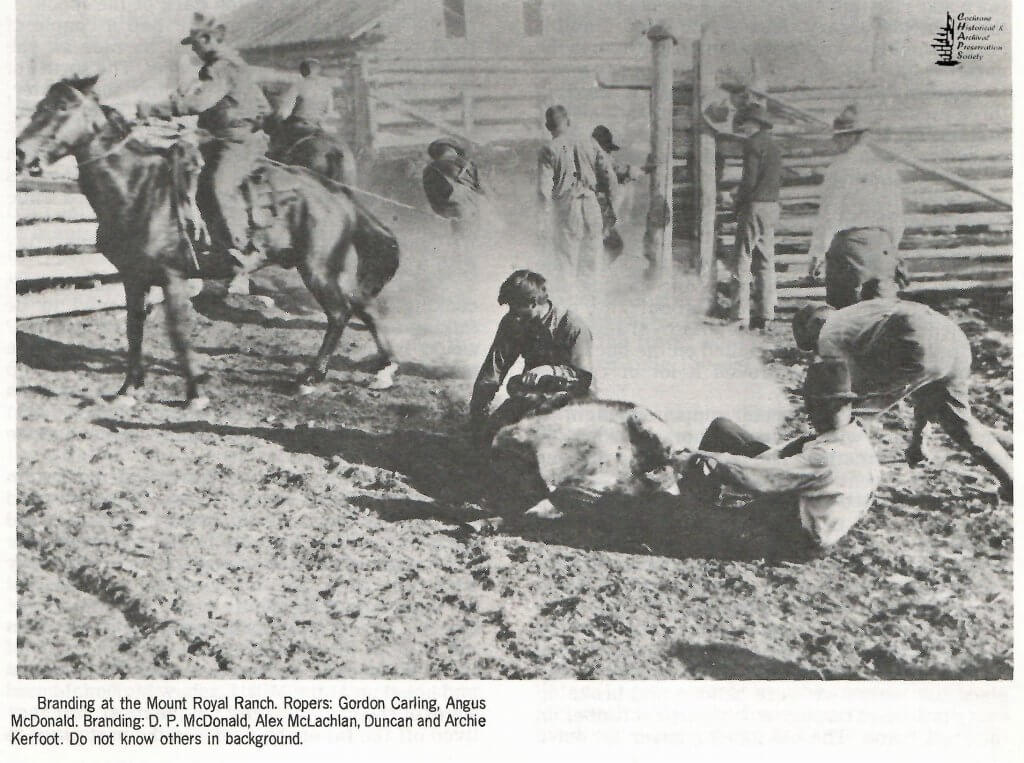

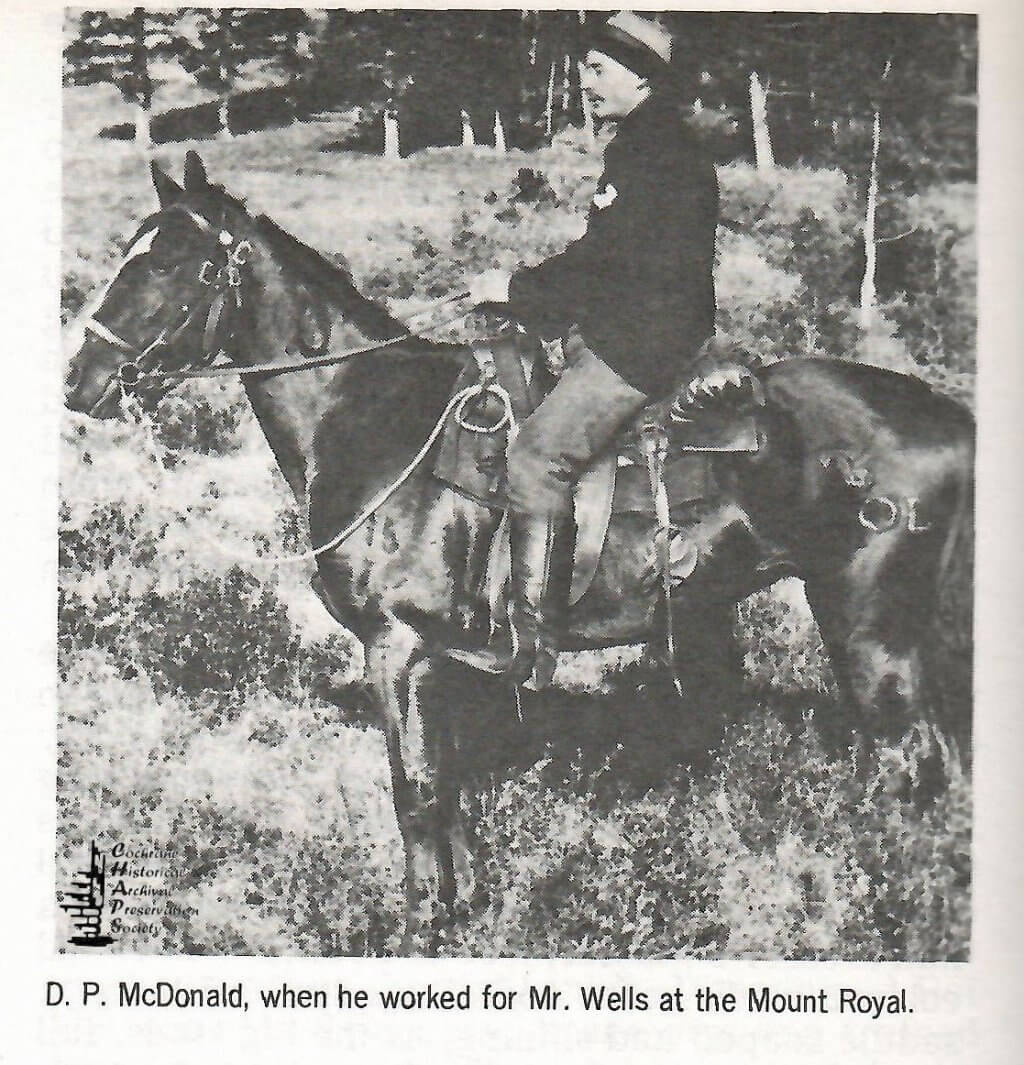

DP must have had more than a little administrative ability to accomplish what he did. He ran two brands: 75 and DP. His cattle ranged over the muskeg and timbered valleys of the foothills as far as the Greasy Plains twenty odd miles to the north. His horses ranged over the same country but as far west as the Sand Hills on the North Fork of the Ghost River. He had calf camps up Big Hill Creek and on the Burnt Ground northeast of Cochrane and camps and range on the Rosebud, a hundred miles to the east. There were no trucks or cattle liners in those days; he trailed his cattle back and forth, bossed the job from a horse’s back and covered more miles a year than a Canada goose. As well as running these several outfits he found time to raise a fair-sized bunch of pedigreed Thoroughbreds, Hunters, French Coach, Clyde and Shire horses, train and race a small string of racehorses, train and show jumpers, hunters, saddle stock and prize studs, ship carloads of polo ponies, hunters and saddle stock to New York and the southern States, butcher his own beef, drive his family to church in Cochrane on Sunday and stage an annual picnic at the Big Springs on Spencer Creek every twenty-fourth of May, which left just enough time to get Brodie to cut his hair and say, “Here’s where I get paid for going through the motions.”

DP raised some good horses and, but for Government red tape, might have had some fame. Shortly after World War I, two government men made a special trip from Ottawa to purchase a chestnut stud DP had raised, which, according to statistics, was the biggest boned Thoroughbred on record. They were authorized to pay DP one thousand dollars for the horse and ship him east where his skeleton was to be mounted in the Ottawa museum. DP had sold the horse a short time before to a neighbouring rancher but offered to buy it back; however, because he did not own it at the time, they refused to take it. A shining example of governmental hair-splitting. Perhaps, of all the horses D Praised or owned he will be best remembered for the Alberta Cow Country’s Aristocrat, “Smokey”, the little high jump champion.

DP didn’t quite deserve all the credit for Smokey. Smokey’s hide should be in a museum but it likely fed a hungry coyote. If it’s still hanging on someone’s fence, you might find a crown brand on the right thigh. Duncan and Pat Kerfoot raised Smokey, broke him and trained him for a polo pony. They did a good job for he turned out to be the best cutting horse in the country and DP bought him for just that. The Kerfoot boys knew he could jump and likely told DP, but, from then on DP deserves all the credit, for he trained the little horse and made him a champion.

I happened to stop at the Mount Royal Ranch the night they got home from the show where Smokey’s record was broken. At supper, that night, Irish, DP’s trainer, and the rest of the boys, were all mad enough to chew nails and spit nickels. In spite of D P insisting it had been a fair contest, he couldn’t shut the boys up. Irish claimed that when Smokey had made his record jump, the top bar had been tied on with two strands of binder twine but when the horse that broke Smokey’s record made his jump, the top bar was buckled on with a double wrap of a flat saddle stirrup leather. Just how great a contribution DP made to Alberta’s Light Horse and horse show industry is hard to say but I doubt if he got more than a small part of the

credit due for the time, effort and expense involved.

The Mount Royal Ranch is fifteen miles or So from Cochrane. Cochrane was twenty-two miles from Calgary by rail. The stock had to be trailed to Cochrane, loaded on cars and shipped to Calgary, Edmonton or elsewhere. You couldn’t turn a bunch of bang tails, show ring stock and prize studs loose and haze them down the trail; maybe you could have, but they would never have looked the same again. They all had to be led separately. Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow might have been bigger but no more spectacular than the Mount Royal Ranch en route to the big show.

First, the Thoroughbreds, led by exercise boys, blanketed if the weather was bad, eager to run, or walking with the long, gliding stride only the Thoroughbred knows. Next, the show ring stock, hunters, jumpers, saddle and harness stock and last, the big prize stallions, fat and slick as seals, their foretops, manes and tails a hairdresser’s masterpiece of French braids and coloured wool, brass and silver studded halters, saddle soaped and shining, as the big studs, full of fight, reared and squealed or, grunted, as the men leading them jerked on the brightly burnished lead chains running through the stud bits to keep each in its place. Strung out half a mile or more along the dusty trail or, through the snow or through the rain and mud for, then as now, the show must go on. Surely a worthwhile effort, as historical as the prairie trail they trod.

Behind every great man is a great woman and Momma D P was all that and more. She loved her horses. To watch the McDonald silks lead the field under the wire, and her two daughters winning ribbons in the show ring, were the great thrills of her life. DP might not have been so enthusiastic had she not loved it so. It was her only luxury, her only extravagance, she loved it every minute and no one deserved it more, for she was a hard-working woman with plain and simple tastes and a heart as big as the whole outdoors.

She’d walk a mile to watch a horse jump, buck or race. Boney Thompson was her favourite bronc rider and she never tired telling of watching him ride a big, brown Thoroughbred mare of D P’s that, she claimed, turned a complete somersault with Thompson scratching sparks out of her ears, laughing and talking all the while.

There was a little paddock around the house to keep the stock away but in the spring at foaling time, Momma DP kept her

Thoroughbred mares there where she could keep an eye on them in case they needed help. They often did and many a Thoroughbred colt would never have lived to carry the McDonald colours but for her gentle hands.

We’d come to the Cochrane district in 1905. In 1910 my folks located on the forks of the Grease Creek and Little Red Deer River and started a small horse ranch. It takes horses a while to range break and for the next few years, it seemed I spent most of my days and a lot of my nights, tracking down horses and trailing them home. I was only ten or eleven years old at that time and a regular customer at Momma D P’s dinner table, usually an hour or two late, but she’d get my dinner and sit and talk to me while I ate. She would ask me all about our place and how many horses we had and when I’d tell her she’d say, “Great God, you’ll soon be as rich as old George Creighton.” I think she enjoyed kidding me but our horses finally range broke and maybe she was as glad as we were. Even at that, we had better luck than old Hughie McDonald.

Hughie and his brother George had a place near Calgary and too many horses. They took out a lease up the Ghost River west of D P’s, trailed their horses up and turned them loose but they were a homesick bunch. Hughie said he could trail them up from Calgary, turn them loose on the lease, ride into Morley, sack his saddle, catch the train to Calgary, take a taxi home and his horses would be waiting for him to let them in the gate.

Besides taking care of a big house, cooking three meals a day for a gang of men and feeding half the riders in the country, Momma DP raised a few hundred geese, turkeys, and chickens. Hunting up the nests they stole away, gathering the eggs, hatching her broods and fighting off the magpies and coyotes was a man-sized job. She kept a few coyote hounds and when they jumped a coyote out on the flat I think she enjoyed the chase as much as the hounds did. Magpies and coyotes were about the only unwelcome visitors at the Mount Royal and some hundred-odd coyote tails nailed on the back wall of the machine shed proved a lot of coyotes learned it the hard way.

My dad and I stopped for supper one night on our way home with a bunch of horses. When she learned my mother had some geese but no gander, she went down to the barn with us after supper, corralled a bunch of her geese, caught a big gander and gave it to my dad. He put the gander in an oat sack, stuck its head out through a hole and handed it to me. I tied the sack to my saddle horn with the old gander half sitting on my off knee. It was early spring and near dark, by the time we got strung out and by the time we got in the timber up the Montreal Valley it was black as pitch. Those horses wanted to go anyplace but where we were headed and broke up every draw and through every patch of timber on the trail home. The old gander never let out a

squawk and ducked the limbs and brush like an old horse thief. I’ll bet he’s still telling his grandchildren of chasing range horses through the Alberta foothills in the dark of the moon.

The fact that Momma DP had a couple of good-looking daughters almost as nice as she was didn’t help DP’s grub bill any. The spring of 1917, while the girls were home for Easter, Marshall Baptie, Laurie Johnson and I were breaking remounts at the lower Bar C. We galloped our broncs out on Beaupré Flats, which was open country at that time. Once our broncs got strung out we’d ride over to DP’s, kid a while with the girls and ride back and get a new string. We could ride out fifteen or twenty broncs a day with a few little visits on the side.

None of us fancied our own or each other’s cooking, so we usually just happened to be talking to the girls about the time Momma DP would come out and say, “Come and set the table, girls, and you boys might as well tie up your horses and stay for dinner.” We took an unfair advantage of her for a week or more, for I doubt if she enjoyed our company as much as we did her cooking.

Not long after the First World War, the bottom dropped out of the cow business. Fall calves sold for three dollars a head, cows for fifteen and horses for a dime a dozen. Folks pensioned their old horses off and turned them loose to enjoy what life they had left, and fur farms and horsemeat packing plants were a curse to come. The slump left a lot of the boys, just back from the war, at loose ends and more than a few of those loose ends drifted into Jack Ass Canyon and holed up at the Mill. Exshaw McDonald paid some of the grub bills but for the most part, they lived off the fat of the land and the best place to get fat in that part of the land was Momma D P’s dining room table. Scarce a day passed but one or more of those loose ends dropped in to help keep D P’s grub from spoiling.

One day, when a couple of those loose ends dropped in for dinner, Momma DP apologized for not having any meat. She said, Donald, has had a beef in for a week but just hasn’t had the time to butcher.” One of them said, “Gee Mrs. McDonald I’m sure sorry I didn’t know, I’d have brought you over some. We had a calf break its leg and we had to butcher it, I’ll bring you over a hindquarter this afternoon.” He was as good as his word but it was one of D P’s calves they’d sidehill butchered a few nights before. Even so, with calves at three dollars a head it was a friendly gesture, typical of the man who made it for he’d have given you the shirt off his back and, taken yours while you slept, yet, the world would be a dreary place but for his kind.

Grub-line riders, or saddle tramps, as they are called today, were, in reality, non-existent in this part of the country. Cowpunchers were a restless lot. The men that graced Momma DP’s dining room table represented most of the Western States. Some had been to the Argentine and back. Even the local boys had worked on ranches scattered over most of Alberta. They’d drop in for a meal, a day or maybe a week, sometimes they’d stay all winter, but they were always welcome and more than earned their keep. They were congenial, capable, and often did more work than a high-priced hired man. Of the “loose ends” that hung around the Mill, those still living are respected citizens today in many walks of life. Most have crossed the Big Divide but they have lots of friends at both ends of the trail. Nor were Momma and Poppa DP the only big-hearted couple in the country, they were one of many. Hospitality was a common courtesy of the open range, but fortunately for the women, now a historical has-been, for it was the women who bore the brunt of the worry and the work.

A lot of water has run down Spencer Creek since those days. The DP picnic at the Big Springs is but a memory. Trucks, tractors and farm machinery clutter the little paddock where Momma DP once kept her Thoroughbred mares at foaling time. No horse wears the DP high on its withers, and Charlie Russell would have starved to death painting the breed of cows that pack the old 75 brand. The old machine shed with the hundreds of coyote tails tacked on the north wall is long gone. There are no flocks of geese and turkeys squawking around the barnyard and the creek is mostly dry. The big barn still stands but no prize studs or Thoroughbreds breast the box stall doors taking playful nips at you as you walk by. The big harness room is empty. The hundreds of ribbons that once adorned the walls are packed away in trunks. Only the wind sighs through the empty loft and sagging doors, mourning an era forever gone.

Momma and Poppa DP have long since taken the trail where the tracks lead only one way but if there is a Short Grass Country in that Great Beyond, five will get you ten, that they are still dishing up grub to a bunch of broken-down cowpunchers, horse thieves and Indians. They’d all be there. Boney Thompson, George Creighton, Charlie Miokle, Ed Johnson, Frank Ricks, Me Track’em, Irish, Paul Beaver and Jonas Benjamin and maybe more, with DP sitting at the head of the table carving half-inch thick slices off a hundred-dollar roast laughing soft at the tall stories being swapped across that red-flowered tablecloth. If there’s an extra place set I hope it’s for me. Progress may be a great thing for the country’s economy but it’s left a hell of a big hole they’ll never, never fill.

Old Cowboy's Dream - by E. Ward Rivard

To all the happy memories of the Mount Royal and Bar C Ranches

Last night I dreamed that I rode once again

With the friends of my youth on that far distant plain.

The friends of my youth, the old friends so dear,

Like music the laughter that fell on my ear. The Rockies arose, majestic and grand,

Like sentinels stationed to guard that fair land. The Bow swiftly flowing beneath the blue sky;

‘Twas a scene ne’er forgot till the day that I die. From the hilltop we gazed o’er the valley below

Where the herds slowly grazed by the sides of the Bow. On far distant ridge there vanished from sight

A bunch of wild horses in fear-maddened flight. The horse that I rode, oh! Strange did it seem

To be riding old Smokey again, in my dream; There wasn’t a doubt, it was plain as could be,

The crown on his hip, on his shoulder “DP.” The creaking of leather, the jingle of spurs

Was sweeter to me than the song of the birds; Down the trail I could hear a voice gaily sing

As we rode the old range on the roundup in spring. Dawn came, and my heart seemed to break with its pain,

When I tried to recall the sweet dream again, To turn back the pages of time

To the days of my youth and the joy that was mine.

Fantastic read…thouroughly enjoyed it!