from A Peep into the Past by Gordon and Belle Hall Vol. 1 pg 50

The railway running across the land and through the mountains was the lifeline of the land, before the railways we had stagecoaches, bull trains and pack strings. Cochrane was one of the villages that depended almost entirely on the railroad, along with dozens of other villages, towns and cities.

Thursday was weigh freight day, and at about 10 A.M. she was due; a small engine and two or three cars of goods for Cochrane and points west. Walter Aris was the dray man (teamster) for many years, so he and his dray and team would be at the station. Carcasses of beef, pork and lamb arrived for the two butcher shops, owned by E. Andison and Andy Clarke. The grocery store goods were shipped in boxes or crates, mostly made of wood; flour in sacks and bananas in crates. The station had a fair-sized storeroom where goods from mail-order houses to residences were kept. People were notified by card in the mail when these arrived. Coal came in by boxcar and was unloaded into coal sheds alongside the track. The UGG Elevator Co. had coal and also Frank Whittle Implement Co., and if the people knew you wanted a load of coal, they would phone you and you could come to town and get it off the car and could save fifty cents to one dollar a ton. Men used to get fifteen dollars for unloading the car, which was just fifty cents per ton.

The steam engines the CPR used were of various sizes and shapes and burned coal until in the 1930s the engines were converted to fuel oil. In the coal-burning days, when the engines pulling the big freights stopped here for water, the fireman of the engine would clean out his firebox and grates and there would be a huge pile of ashes and clinkers to be hauled off by the section men. They did this with wheelbarrows and planks. The smaller engines pulled the way freight and passenger trains and the famous Silk train, when a boatload of silk arrived in Vancouver harbour, it had to cross Canada to the eastern provinces to be manufactured into cloth, and because it was perishable, the silk had priority over everything, passenger trains and all.

We used to find out from Gainor, the agent, when she was due here, then stand on the platform. She was doing a cool 70 mph and there was noise dust, cinders and steam flying. We, as kids, thought it was great. When trains were travelling through, without stopping, orders were relayed to the engineer by the stationmaster with a stick, with about a 2-foot loop at one end with a clip to hold the written orders, the station man would stand alongside the track and the engineer would catch the stick on his arm, take off the order and toss the stick onto the platform. The late F.L. Gainor was stationmaster for a considerable length of time at Cochrane Station. Section foremen I remember were Fred Grabas and Steve Matkoluk.

When the depression hit at the beginning and during the 1930s, hundreds of men rode on the freight trains, men looking for any kind of work, hungry and dirty with old clothes on and a bundle with their worldly wealth. There were so many railway police who usually left them alone. Here in Cochrane, if the mounties’ woodpile was low, he would arrest a couple of men riding a freight, get them to cut him some wood, buy them a meal and turn them loose.

In the late 30s and early 40s, the train engines were converted to oil, doing away with the cinder piles and the clean-up of cinders along the track. However, the handwriting was on the wall, so to speak, and soon the steamer was discarded for the modern diesel engine. The diesels moved the trains cheaper and with less effort, but like everything else, it took the romance out of railroading.

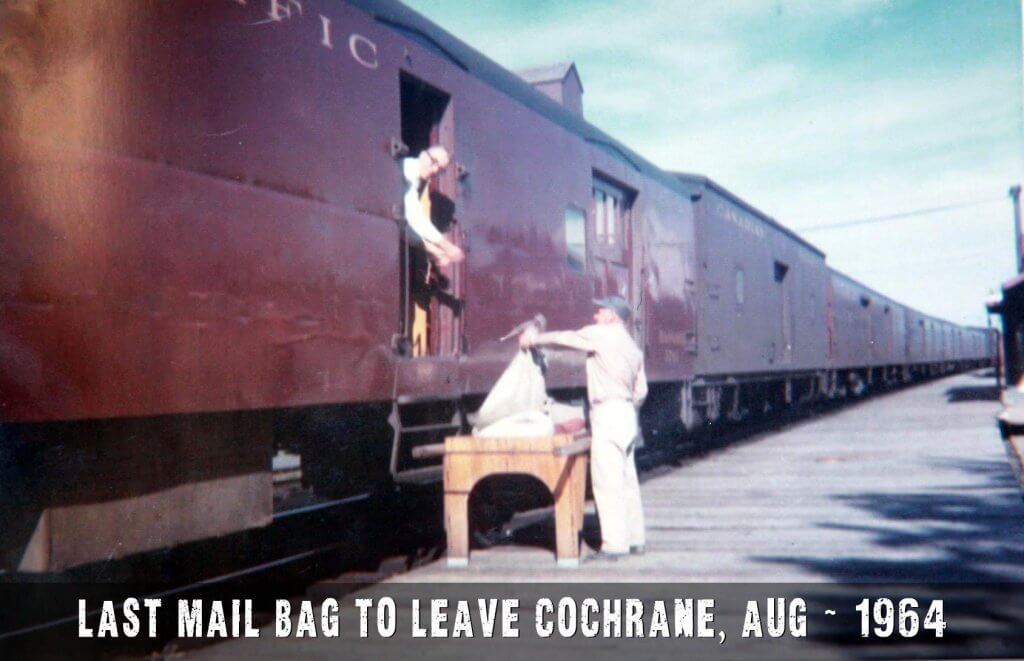

The last mail to go by train from Cochrane was in August 1964, and since then, goes by truck. The Cochrane Station is long gone, the CPR just dug holes with bulldozers and pushed it in and buried it.