from Big Hill Country

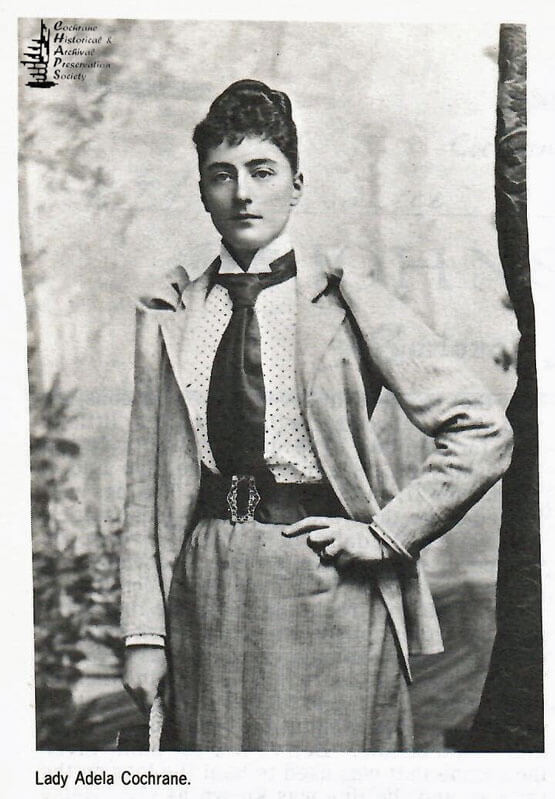

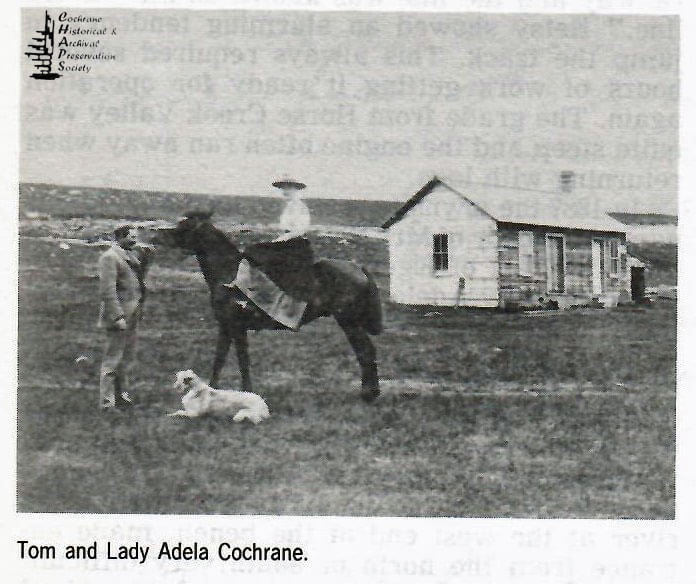

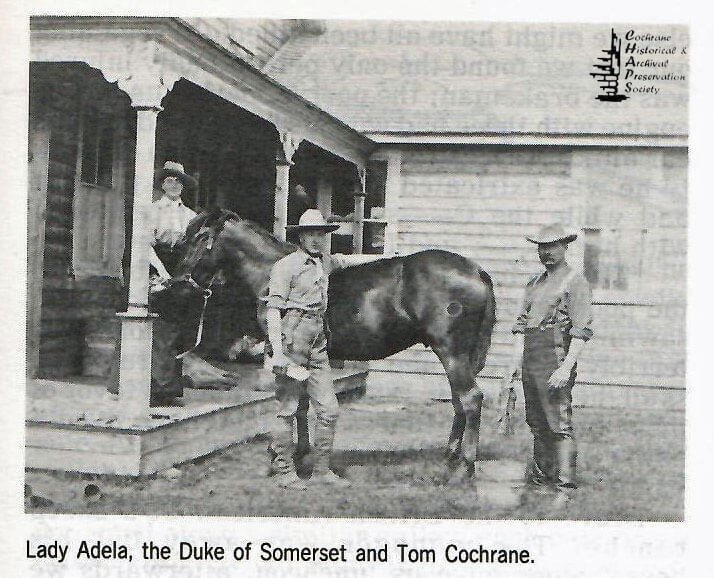

T.B.H. Cochrane, son of Admiral Sir Thomas Cochrane of England, and his wife, Lady Adela Cochrane, daughter of the Earl of Stadbroke, were the founders of Mitford. The Cochranes were a remittance family that had come to Canada in 1883. They went to the High River area and acquired a large ranch lease of fifty-five thousand acres. This was southwest of High River, centred on Township fifteen, Range four. In 1885 they exchanged this lease for one around Township seventeen, Range six, west of the fourth meridian. There is no record of the leases being stocked. In 1886 the Cochranes decided to enter into the lumbering business and chose the subsequent site of Mitford to set up their sawmill business.

Early in 1886, Tom Cochrane completed his sawmill. It was located three miles west of the present town of Cochrane, on the north side of the Bow River, a short distance from the point where the Canadian Pacific Railway crosses to the south bank of the Bow River. The sawmill was capable of turning out thirty thousand board feet of lumber per day, Tom Cochrane was associated with Hugh Graham, Francis White, and Archibald McVittie of the Calgary Lumber Company and contracted to supply them with lumber. Plans were made to build a rail line from Grand Valley to the sawmill but in the meantime, logs had to be hauled by teamsters, The sawmill went into operation in July 1886. A small steam engine was purchased and work began on building the track. This track was laid northward up Horse Creek Valley for one mile and then westward to Grand Valley, where a turnabout for the engine was built. The remainder of the track was made of wooden rails and extended northward to the Dog Pound Creek. Small horse-drawn cars were used to haul the logs along the wooden railway to the turnabout.

There were several small stands of fir on the west side of Grand Valley, about five miles north of the Bow River. However, the ties and rails required for the wooden track very nearly used them up. Further north, on the Dog Pound, the timber was mainly spruce and pine. The result was that the best timber was used for the construction of the railroad and there was very little fir left for lumber. The timber limits lay in Townships 27, 28 and 29, Range five and in Townships 27, and 28 in Range six. The logs were hauled down the wooden track by local settlers who worked at a daily wage. The men were poorly supervised and the enterprise, as a whole, was poorly organized. The cars were continually jumping off the track and since the men were paid regardless of the amount of work done, no one helped the teamster whose car was derailed. The result was, hours were spent in idleness waiting for the track to be cleared. “Betsy” would be kept waiting at the turnabout and the mill would be idle. “Betsy” was the name given the engine that was used to haul the logs on the railway and the line was known as the “Betsy line.” Betsy showed an alarming tendency to jump the track. This always required several hours of work getting it ready for operation again. The grade from Horse Creek Valley was quite steep and the engine often ran away when returning with logs.

In 1887 the townsite received its name. It was named in honour of Mrs. Percy Mitford, a sister of the first Earl of Egerton. Mrs. Mitford was a friend of Lady Adela and also had a financial interest in the Cochrane enterprises.

The site that Tom Cochrane chose for the little town was very impracticable. It was at the confluence of the Bow River and the Horse Creek, on a low bench some two hundred yards wide and one half mile long. The steep hill to the north of the river and the townsite abutted on the river at the west end of the bench made an entrance from the north or south very difficult. Horse Creek Valley was narrow and it required considerable labour to build the grade for the “Betsy Track.” On the east, the Canadian Pacific Railway occupied the only good approach to the town, and it too was on a sharp incline. At Mitford, the railway and the river came together on a long angle and as a result, the flat between the river and the railway was very narrow. It was on this flat that Tom Cochrane built a store, hotel and a saloon. The only ford across the river was treacherous and of course, horses could not be taken across the railway bridge. On the south side of the river, the hills rose sharply and there were no satisfactory building sites. There is a certain picturesque beauty about the location but as a townsite, particularly a town that was hoped would expand, it was quite impossible.

In the year 1888 several buildings were erected, among them a livery stable, as well as the store, and hotel. Prior to that, the Cochranes had built their own home, and several bunkhouses were erected for the men working in the sawmill and the coal mine. There had been some private homes built; these no doubt were for the people that operated businesses there. In 1889 Mitford received a Post Office. The first doctor to arrive in the area was Dr. Hayden who had come in 1888. With the sawmill going and the accidents on the Betsy Line, no doubt the doctor was kept busy. He operated a small drug store in connection with his medical practice.

In the year 1888, a fellow by the name of de Journal operated the store and hotel for Tom Cochrane. In 1890 the sawmill was closed down; it was not a success from the start. Count de Journal left the employ of Cochrane in 1890 and was succeeded by R. Smith in the hotel and A. Martin in the store. Mr. Smith had worked in the sawmill for three years before he started in the hotel. His daughter, Violet, was the first child born at Mitford in 1890. His daughter, Sadie, married L. V. Kelly, author of the book, “The Range Men.”

Their father was a section man at Radnor and later became a rancher at Jumping Pound. Harry Jones and George Skinner, sons of ranchers north of Cochrane. Birdie Radcliffe, whose father operated a creamery at Big Hill Springs, and Mary, Everett and Joseph McNeil of the John McNeil family.

Miss Monilaws taught school for four years and in 1895 married J. Cooper. Mr. Cooper had been employed by Tom Cochrane at the mine and the sawmill and later at the brickyard. At the time of their marriage, Mr. Cooper was living on his ranch a few miles northwest of Mitford.

The Cochranes, having failed at the lumbering and coal mining ventures, decided to go into the manufacturing of bricks. The clay was hauled from a flat, two miles north of Mitford, by the locomotive. The brickyard consisted of three kilns, of a primitive type, and a number of drying sheds. Mr. Cooper was in charge of the yard. The bricks were of poor quality and expensive to make. The enterprise lasted two summers.

Doctor Hayden had left Mitford in 1891 and Mr. Cowley came to take over the drug store. Joe Howard built a blacksmith shop one-half mile east of Mitford on the north side of the C.P.R. line. Tom Cochrane decided to build a bridge across the Bow River. It was located one hundred yards east of the railway bridge and consisted of two spans abutting in the middle of the river on a small island. It was a toll bridge for a short time, the fees being five cents for an individual to walk across and ten cents for a team and wagon.

In 1892 an Anglican Church was built on the hill northeast of the town. Lady Adela collected funds in England and she herself contributed some money to build the church. Many of the furnishings were given by Lady Adela.

The brickyard was the last business venture of the Cochrane family in this area. It was abandoned in 1893. Betsy was sold to a lumber mill near Golden, British Columbia. The track was taken up and the industrial life of Mitford came to an end. The C.P.R. had never liked to stop at Mitford at any time and finally cancelled regular stops there in 1893. Trains proceeding east and stopping at Mitford were forced to back up a half-mile in order to make the grade out of town. Westbound trains always came to a halt with the engine on the bridge and this was dangerous. The local children soon discovered that a small amount of grease applied to the track caused some worry to the track crews, especially when the trains were going west; they slid right through the town before they could stop. The next three years saw the final abandonment of Mitford. Mr. Martin and Mr. Howard moved to the town of Cochrane and started businesses there. Tom Cochrane decided to enter politics and he ran against Frank Oliver in the election for the House of Commons in 1896 and

was defeated. Shortly after that, the Cochranes returned to England. Tom Cochrane’s sister was a Lady in Waiting to Princess Beatrice of Battenberg. The Princess was Governor of the Isle of Wight. Tom Cochrane’s sister managed to get an appointment for him as Deputy Governor. By 1898 the town of Mitford was deserted, the fire had destroyed many of the buildings and most of the population had left. The Anglican Church was moved to the town of Cochrane and is still there today. All that remains of Mitford is the tiny cemetery on the land where the Anglican Church once sat. The cemetery and the church were on an acre of land purchased by the church in England.

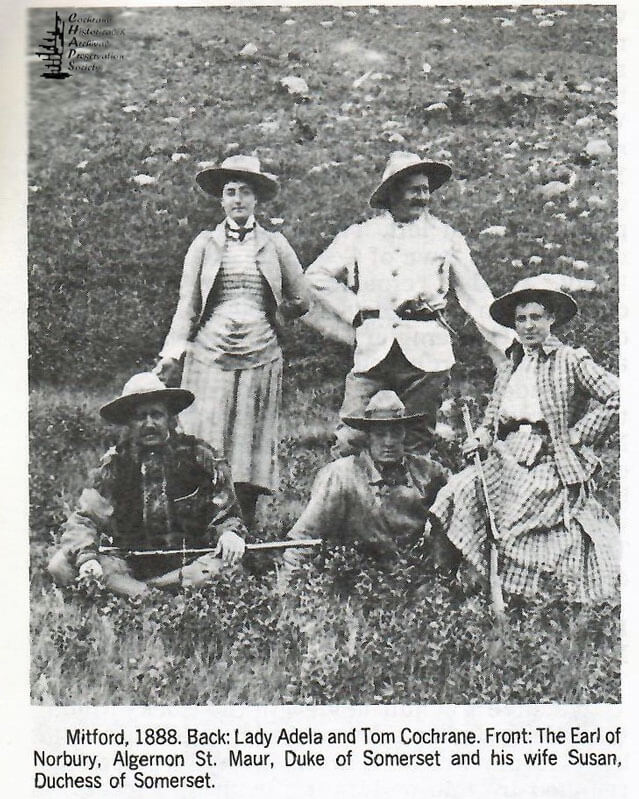

Included in this story of Mitford are excerpts taken from the diary of Mrs. Algernon St. Maur. Mrs. St. Maur was a friend of Lady Adela and came to Mitford to visit the Cochranes. After going back to England from a visit to Mitford, she wrote the book “Impressions of a Tenderfoot.”

The book was published in 1890 and the excerpts are from that book.

FROM THE DIARY OF MRS. ALGERNON ST. MAUR

“May 31st. We have a beautiful view of the Rocky Mountains here, and on a fine morning it is difficult to believe they are sixty miles away; we are surrounded by fine undulating prairie. The cattle are fat and sleek, though they have had nothing but what they could find on the range all winter. The great drawback here is the frost at night, even in summer there is often enough to injure the potatoes and wheat. Adela and I amused ourselves planting the garden; we sowed cabbages, lettuce, cauliflower, carrots, beets and beans. The soil is surprisingly rich; one digs nearly a yard deep and still it is the same good brown loam.

“The sawmill and the house are close to the C.P.R.; at the former fifty men are at work. Their wages are from twenty to thirty dollars a month, and they are boarded as well. A private railway brings the logs down from the forest, they are sawn up here and put in the cars for market.

“N–, Tom C– and Algernon have been busy this morning making a garden fence. They are also building a new hen house; the latter requires to be well put together, to keep out the cold in winter and has double walls with sawdust filled up between. Dug out hen houses with turf also make warm shelter, only a few have stoves, and often the claws of the poor birds get frost Bitten. The cat here has had her ears frozen off; fortunately they are both gone just at the same place, and give her the appearance of having her ears cropped.”

(Tom C was Tom Cochrane and Algernon was her husband, Mr. St. Maur. N remains unknown, although it is possible that he was the Earl of Norbury who lived for a time with the Cochranes.)

“June 1st. Mr. Kerfoot, a neighbour, and one of the best riders and drivers in the northwest drove Adela’s ponies on the buckboard. They have been on the prairies for six months; when taken up they often require rebreaking. One of them lay down twice, bucked, and made a great fuss. Mr. Kerfoot drove them patiently and well. The harness and buckboard both of American make were perfectly adapted to the rough roads and prairie work. These carriages, owing to the wide axle, are almost impossible to upset, and one can drive them where no English carriage could go. The harness enables the horses to go quite independently of each other; the pole pieces, instead of being, as in England, fast to the head of the pole, are here attached to a short bar called the yoke which works loosely on the end of it, and also gives the horses a straight pull in holding back.

“We all started on the private railway to see the timber limits, which are fifteen miles distant. A truck was arranged for us to sit on in front of the engine, the latter pushing us along. The men in charge drove too fast, and when we had gone about three miles we felt several great jolts, the truck had left the rails and upset; most fortunately for us, one of the wheels got wedged in the sand and the brakeman, having put on the brakes, stopped the engine. For a few moments, there was an awful feeling of suspense; we all expected the engine would come crashing down on top of us; happily, however, this did not occur,

else we might have all been killed. On regaining our feet we found the only person badly injured was the brakeman; the poor fellow lay under the engine with three bad wounds in his head and his ear almost severed from the scalp. With difficulty, he was extricated from his perilous position and while the C–s and Algernon remained with him, N– and I went for assistance.

“The Doctor came quickly, a wagon followed, the poor fellow was soon in his little bed at the sawmill, and wonderful to relate, though so terribly injured, and with a badly fractured skull, he recovered. It is always much in favour of these men during an illness that they have lived a hardy out-of-door life.

“June 2nd Drove to the British American Co’s sheep ranche. The manager was away but his housekeeper gave us a luncheon, afterwards, we went fishing.

“June 4th Ten degrees of frost last night. Algernon went for a ride with Mr. Kerfoot, and in the afternoon we all rode over to his horse ranche. The horses are most clever in avoiding the gopher holes, and if given their head they can go at any pace over them without making a mistake. At the ranche we saw more than a hundred horses. The corrals are wonderfully arranged, three openings into each other. When the band of horses has been driven into the first which is the largest, the horses required for branding or breaking are separated from the rest and the gate being opened, is turned into the second corral. The entrance into the third corral is by a very high strong gate, so arranged as to swing around against the side of this corral with just space for a horse to stand between. A single horse is now let through this gate, which is swung around holding him against the side of the third corral so that he is helpless and cannot fight or hurt himself being branded or bridled.

“June 6th On the other side of the Bow River is a canyon known as the Jumping Pound, over the edge of which the hunters used to drive the buffalo, and in this canyon, their bones still lie in places two and three feet deep. They are now being taken away and used for manure. A band of Blackfoot Indians passed today; the Chief, “Three Plumes”, rode up to the house to show his permit, which is given by the Indian Agent to enable them to leave their reservations for a stated time; this band had been on a visit to the Stoney Indians. (We have since heard that the guests on leaving stole thirty horses.)

“June 14th Until this morning we have not seen the Rockies for a week. Innumerable wildflowers grow on the prairie; last month there were anemones of all colours, and in a few weeks there will be masses of dog rose and wild honeysuckle; it is a kind provision of nature that this wild rose is so hardy, it stands even the extreme cold of

winter and grows from the root each year. The doctor, who is a botanist, sent a collection of wildflowers which he had made, to Kew Gardens to be classified. We went to see the coal mine that was discovered three years ago, the first traces of coal being seen at the mouth of a badger’s hole. Adela and I only went in as far as the first galley, where we met a man and horse bringing up a truck of coal to the mouth; the others all departed along with a similar galley, each carrying a Davy lamp; as yet there is little danger of gas, the workings being quite near the surface.

“June 18th Adela’s sitting hens require a lot of running after, half-wild and fleet as hares, they appear to have a strange dislike to returning to the nest, so we have to get some of the men to help us run them down. Two ranchers came to luncheon today – true types, I should think, of Western men. I hear that their father in England is a rich man, but he seems to do little for his sons. They work hard, even washing all their own clothes and cooking, and it is not therefore to be wondered at, that they look rough. The usual dress out here is a blue flannel shirt, with no collar, but a coloured handkerchief tied loosely round the neck, a buckskin shirt, a pair of leather chaps with fringes down the seams, worn over trousers, boots and a broad-brimmed felt hat with a leather band around it, which is generally stamped with patterns and ornamented in some way.

“June 21st Today we visited the forest or timber limits, starting early. The ride was quite delightful, as we cantered up and down these limitless plains of grass, with the mountains stretching away into the dim distance as far as the eye could reach, and extending in Canada alone for eight hundred miles. Tares of many shades, pea vine, wild camomile, bugle flowers and many other wildflowers we saw as we rode along, also myrtles, gooseberries and dog roses. Occasionally a few prairie hen rose in front of us, and flew away, wondering doubtless at having been disturbed. As we came into view of the log house where some of the lumbermen live, we saw the forest beneath us. We rode four miles further, over somewhat marshy ground, then after descending a rather precipitous path, we found ourselves at a place which goes by the name of Dog Pound Creek; the horses were all picketed out, the harness and saddles having been removed.

Madam d’Artigue and her husband and sister (French people from the Basque Provinces) are in charge of this ranche for someone who lives in Calgary. It was quite a pleasure to see their beautifully managed poultry yards. There were hundreds of chickens of all ages and sizes, rows of boxes for the sitting hens with one hen in each all arranged the same and in a practical manner peculiar to French people. There is an excellent market for poultry in the northwest; they told me that for a capon they got one dollar and seventy-five cents in Calgary.

“June 24th-Sunday, In the evening we had a service from a travelling minister, about half the men came; the hymns selected by him were not at all cheerful nor bright, and his sermon was not suitable in any way to the requirements of his listeners, which one regretted.

“June 25th Rather a tragic termination to our visit was caused by another accident on the railway. In the evening we heard the mill whistleblowing violently, and found that the engine, returning with four trucks of lumber, had been thrown off the rails; the engineer got jammed between the engine and the logs, and had his leg broken in two places; but such is the toughness of these men that when being carried down we heard him joking with the others about not yet needing to be carried feet first, though he must have been suffering great pain.”

amazing stories – thank you to all involved!

A very interesting article. The R. Smith mentioned was my grandfather Richard [Dickey] Smith and is buried in the Mitford cemetery.

Y’all probably know, Shannon Bradley-Green (Stu Bradley’s daughter) wrote a book on this very subject