ANDREW SIBBALD - by John and Beryl Sibbald pg 780 Big Hill Country

Andrew Sibbald, whose life spanned a century, was born in Ontario, November 19, 1833. Andrew’s father, John Sibbald, along with his wife and three children of Edinburgh, Scotland, immigrated to Canada in 1832 and settled in Ontario. Andrew was the first of their five children born in Canada.

In June 1875, Andrew Sibbald with his wife, Elizabeth Ann Robins, and their three small children left Stroud, Ontario, to seek a new life in the West. Andrew and his family left Bramley Station on the Northern Rail. They took passage on the Steamer “Frances Smith” and proceeded to Owen Sound, where the Sibbalds joined Rev. and Mrs. George McDougall, their son George; two nephews, George and Moses McDougall; Mrs. Hardisty and her two children, Clara and Richard; Miss Young, who was bound for Edmonton to visit a brother; Mr. and Mrs. R. G. Sinclair; and Rev. and Mrs. H. M. Manning. At Prince Arthur’s Landing, now Port Arthur, the party changed onto the “Quebec ” of the Sarnia Line, bound for Duluth, Minnesota. They then left by the Northern Pacific Junction to Moorhead and from there proceeded down the crooked and muddy Red River to Fort Garry, a distance of five hundred miles. At this point, they were joined by David McDougall, who was to act as a guide for the journey of nearly nine hundred miles across the plains.

Provisions, horses and oxen, wagons and Hudson Bay carts were purchased at Fort Garry. After all, was ready, the caravan set out. travelling ten to fifteen miles a day, and always resting on Sundays. “We forded all streams in our path,” Andrew Sibbald recalls, “except the South Saskatchewan, which we crossed in a scow.” David McDougall and Andrew kept the travellers supplied with fresh meat. Ducks, geese and prairie chicken were plentiful, but as the hunters had no dog, they were forced to wade the sloughs and streams to retrieve any game

they shot. In this way, they walked more than two-thirds of the distance from Fort Garry to Morley. They were caught in an early blizzard east of Buffalo Lake on October 3 and forced to make camp. Lacking dry wood they had to collect buffalo chips for fire and dine on pemmican and dried meat. After three days the journey was resumed in two and a half feet of snow. After passing Fort Ellis there was no sign of civilization until on October 21, they arrived at Morleyville. The course laid well to the north, as they wanted to keep away from the Blackfoot country along the Bow River. By the time they reached Morleyville, having taken 104 days from Barrie, Ontario, the trail was like a half-circle, with the bend to the north.

Andrew had trained as a master carpenter in Ontario. After an accident in which he lost his left hand, he trained as a teacher. It was in this capacity that he accepted a position as an instructor to the Blood Indian Tribe. He was, however, still skillful as a carpenter and had brought west the all-important parts for a sawmill. Andrew, with the help of willing hands, soon had the sawmill assembled and in operation. The school, church and other necessary dwellings and buildings were erected. A village, with a population of approximately five hundred Indians [sic], seemed to appear from nowhere. Sibbald’s sawmill was the first in the district and he supplied lumber for the first church to be built in Calgary. The lumber was floated down the Bow River from Morley to its destination.

The women who came west in the early days faced many hardships. Often in history books, their role is underplayed. On the journey west, Mrs. Sibbald had in her care their three young children, Howard, nine years old, Frank, six and Elsie, three years. Their youngest son, Clarence (Bert), was born after they came to Morley. In 1882 Mrs. Sibbald became ill during a typhoid epidemic in the settlement. Young Albert Boyd made an epic horseback ride to Fort Macleod for a doctor. Despite the round trip made in eighteen hours, using relays of horses, Mrs. Sibbald died of typhoid. Her youngest child was still only a baby.

For a number of years, until retiring from teaching in 1896, Andrew taught the Indian [sic] children. He taught the subjects which would help them most, the three Rs — “reading, ‘riting and ‘rithmetic.” He stressed manliness, honesty, trust in God and respect for one’s fellow man. His own children attended the school and they learned to speak Stoney fluently. Andrew Sibbald was the first schoolteacher in Alberta. As a tribute to Andrew, two schools, one in Cochrane and the other in Calgary have been named in his honour. Andrew was also Superintendent of the Sunday School at Morleyville. He was a loved and trusted friend of the Indians [sic].

Andrew homesteaded on the hill north of Morleyville, on the W 1/2 30-26-6-5. Ripley Creek rose from a spring on his north quarter. On the

home quarter he built a large log house. His brand was the Triangle on the left thigh for horses and 2VT on the right rib for cattle.

In 1892 his daughter Elsie married a young Englishman, Bertram Alford. He took her to live on his homestead on the Little Jumping Pound Creek, the present site of the Sibbald home place, but the young couple stayed only a short time before moving to Pine Lake, Alberta. The homestead was taken over by his brothers-in-law, Frank and Howard Sibbald, to add to their adjoining homesteads.

Upon retiring, Andrew moved to the ranch in 1896 and built a cabin that is still there, and in livable condition. He later moved to Banff but spent the winter months with his son Bert in Cochrane. Andrew was honoured on his 100th birthday, which he reached, well in mind and body. The Old-timers Association presented this address to Andrew Sibbald:

“You are today privileged to enjoy the unique distinction and honour of celebrating the one-hundredth anniversary of your birth. Such an honour is rare in human life, and your legion of devoted friends throughout the province join in extending to you their heartiest congratulations and good wishes.

“Your long life of unselfish service, devoted to the upbuilding of the Province of Alberta, in which you have resided since 1875, the trials and hardships borne by yourself and family during pioneer days cannot fail to be an inspiration to other generations, as they have been to the present.

“For the contribution, you have made in laying the foundations of Christian civilization in Alberta, we express our sincerest gratitude coupled with earnest prayer, that the Great Giver of all Goodness, who has watched over and guided you during the past century, maybe your constant future guide.”

Andrew died at Banff on July 13, 1934, and was buried at the Millward Cemetery at Morleyville. Andrew Sibbald, during the fifty-nine years spent in Alberta, left large footsteps for future generations to follow.

ANDREW FRANKLIN SIBBALD - by John and Beryl Sibbald

Andrew Franklin (Frank) Sibbald, born in 1869, came west with his parents in 1875, at the age of six years. His early education was obtained on the Stoney Indian Reservation at Morley, where his father, Andrew, was the teacher.

Having practically grown up with the Indians [sic], Frank learned to speak their language and became a very true and trusted friend. In recognition of his hunting skills, the Indians [sic] gave him the name “Tokuno meaning “The Fox.”

Knowing the country and mountain trails well, Frank was guide and packer for the survey crews of the C.P.R. in 1882-1883. Frank and his brother Howard was with Steele’s Scouts in the 1885 Rebellion.

In 1893 Professor A. P. Coleman, author of “The Canadian Rockies,” made his third trip toward Mt. Brown, taking with him young Frank Sibbald as a packer and handyman. In that book he wrote, “Sibbald was hardy and resourceful, as Western ranchers are apt to be, was thoroughly familiar with horses, and a fair camp cook, so he served our purpose admirably, though he had seen little of the mountains and did not profess to be a climber.

“Living in Morley as a boy, he had learned the Cree and Stoney languages from Indian [sic] playmates, so he could talk to the Indians [sic] we met

or travelled with, and pick up useful information from them.”

Professor Coleman also wrote that “Frank Sibbald was worth as much as two other packers put together. He was not only an excellent horseman but was as skillful in tracking a strayed pony as an Indian [sic], and his uniform readiness and good humour added much to the comfort of the journey in which every side of a man’s character and physique is often sorely tried.” Professor Coleman was happy to learn that Frank Sibbald became a prosperous rancher.

In 1893 he married Janet Emily Johnstone, “Jennie,” daughter of a pioneer family. Jennie was born in California and came to the Cochrane area in 1884 with her parents, Mr. and Mrs. James Johnstone. Frank and Jennie were married in the Anglican Church at Mitford. After a wedding breakfast served at the home of Lady Cochrane, they went to live on Frank’s homestead on the Little Jumping Pound Creek. When Frank was away from home, Jennie would keep the table supplied with fresh game and fish. Frank’s cattle brand was The Compass, on the right side for cattle and Jennie’s cattle brand was JS on the right rib.

In 1915 they enjoyed a trip to California, where some of Jennie’s family lived, and while there learned to play tennis. They so enjoyed the game that upon returning home, they built a tennis court that was enclosed by high wire and had a packed base of fine gravel. This court was

enjoyed by the family and neighbours and was the setting for many lively matches.

Frank helped at the Calgary Stampede, particularly with the Indian Village. He was also one of the principals in the organization of the Lord Strathcona Horse and was instrumental in the building of the Jumping Pound Community Hall.

The Sibbalds were also active in the Banff area. Frank helped with Indian Days. They owned the Hussey bungalow, corner of Moose and Banff Avenue, where they always had open house during the Banff carnivals.

The collecting of Indian [sic] curios and handicraft work was one of Frank’s hobbies. Many of his most valuable pieces were presented to him by members of the Stoney Indian Tribe in appreciation for acts of kindness on their behalf.

An 1895 account book is interesting for the prices listed. The wolf bounty was $3.12; horseshoeing was 50¢; overalls $1.00 a pair and boots $1.75. While a bobsleigh was $30.00, you could buy a load of oat hay for $6.00. In the food market, beef was six to eight cents a pound; bacon 12¢; butter 20¢ and a barrel of apples $6.25. During the depression years, Jennie sold a small cow and with the money bought a dishpan and teakettle. Cows were selling for a cent a pound!

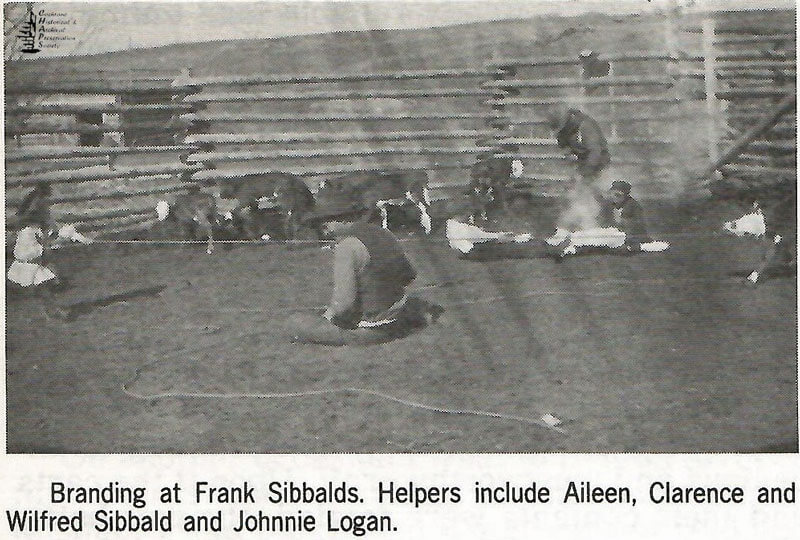

Frank and Jennie had three children: Clarence born in 1896, Wilfred in 1897 and Aileen in 1902. The three children carried on the ranching operations which Frank and Jennie started. Frank passed away in 1941, and Jennie in 1949.

Frank Sibbald’s love for his ranchland passed from him to his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. His descendants continue to enjoy and be a part of, the good life along the Little Jumping Pound Creek.

HOWARD EMBURY SIBBALD 1865-1938

A personal narrative by Howard Sibbald, written for the Alberta Old-Timer’s Association in January 1923. The article is printed with the permission of the Archives of the Canadian Rockies, Banff, Alberta.

In the early part of the year 1875, my father, Andrew Sibbald, had been offered a position as teacher to the Blood Indian tribe in the far west. This offer he accepted and so, at the age of nine years, I, in company with the other members of our family, left Stroud, Ontario, on the 10th of June 1875. The party consisted of my father and mother, a brother Frank aged 6 and a sister Elsie aged 3.

Travelling by way of Duluth and Moorehead and from there descending the Red River we presently completed the initial stage of our journey by reaching historic Fort Garry. Here we met David MacDougall with his cart train with whom we were to travel into the interior. My father purchased a horse and a light wagon for us to ride in and also secured a cart together with an ox to haul it. In this ox cart were loaded all our personal goods and chattels together with a sewing machine and an organ. This instrument was, I think, the first of its kind brought into the North-West, although some years previously the MacDougall family had imported a folding melodeon.

Leaving Fort Garry we set out across the prairie, our faces toward the setting sun. To me, a nine-year-old boy, it was a journey of adventure and withal an experience never to be forgotten. Father walked most of the way and with his gun kept the party supplied with meat and game. There being no dog in the outfit I was frequently obliged to act as a retriever, wading into the sloughs for ducks which had fallen to the gun. The game was plentiful at that time and we never lacked fresh meat.

Travelling on the Old Edmonton Trail we saw no white man until at a point near Bird Tail Creek (now Birtle) we encountered a survey party in which was Mr. Alan Patrick, now of Calgary. This meeting happened on a Sunday and both outfits observing a day of rest, we had an opportunity to learn much about the country through which these men had recently come.

Long before we reached Fort Ellis our freight ox had become exceedingly footsore and weary so my father traded him off for a partly broken steer. The part which had been broken must have consisted of a very small fraction of the animal because he proved to be an unruly fractious beast upsetting the cart several times. After a few days, my father paid MacDougall to bring our freight along in his train. My mother drove the horse and looked after us children who, sheltered from sun and rain beneath the cover of our wagon, looked out in wide-eyed wonder at the various forms of wildlife then so abundant on the open prairie. Father was quite unfortunate in his choice of draught animals as this horse of ours turned out to be a restless nervous brute. If left standing too long it would become impatient and on several occasions caused considerable alarm by bolting across the prairie, bouncing us youngsters around in the wagon and giving Mother an anxious time until she was able to get it under control and back into the line of teams and carts again.

The first Indian [sic] we saw came into one of our wayside camps in the evening. Mother was busy preparing pancakes for supper. The Indian [sic], being somewhat of a curiosity to us, was invited to partake of the hotcakes. This he did, bolting them as fast as the astonished cook could turn them out of the pan; while we hungry youngsters watched with awe and wonder the rapacious Redskin [sic] devouring what was to have been our evening meal. This incident was indelibly etched on my memory and I can still recollect that after dark on that evening I lay watching the stars and speculating on just how many pancakes an Indian [sic] could eat were he presented with an unlimited supply of the toothsome edibles.

After a long and somewhat tiresome journey, we finally reached the foothills and made preparations to spend the winter in the little settlement at Morley. The untimely death of Rev. George McDougall which happened during the winter was an irreparable loss to our small community and had the effect of delaying for several years the establishment of a mission school amongst the Blood Indians. So my father stayed on at Morley, where for some years he taught school and at intervals engaged his time at such seasonable occupations as were to be had in a small rural district far removed from civilization. In later years, when the family had grown up and could be of real assistance, we engaged in ranching near Morley.

In the early period, all our supplies had to be brought in from Fort Benton. As only one trip was made each year, a considerable train of carts was needed to export hides and furs and to import the necessary food and supplies upon which the settlement depended. So in the spring of 1876, I was quite excited over the prospect of going with the annual supply train to Benton. Our caravan was composed of some forty vehicles. In addition to the animals necessary for hauling the carts, we had a number of unbroken steers, which were to be initiated into the art of hauling in harness as we proceeded on our outward journey. These would then be of service in bringing home our bulkier and heavier imports. These steers were, to say the least, ornery brutes and could only be handled to any purpose when coupled with a steady ox accustomed to the collar. On this trip, I was appointed tutor to a steer hailing from Texas. His horns were long and his list of good qualities was short. My first attempt to lead him nearly proved my last. I was very much afraid of the big hulking brute, so, climbing into a cart to which an old ox was harnessed, I tied the steer to the back end, the other end of the rope being attached to his horns. When the cart ox started ahead Mr. Longhorn reared up on his hind end and brought his fore-end crashing down into and through the bottom of the cart in which I cowered. After recovering from this scare, I persevered with him and soon he was as docile as any animal in the outfit. An ox team depended on a

great deal on a steady reliable lead animal. A team consisted of six oxen, each one harnessed to a cart. The teamster in charge either rode in the first cart or led the ox at the head of the string. The other animals being tied to the back of the preceding cart were kept in line on the trail.

Crossing rivers that were too deep to ford, proved to be a tedious undertaking on such a trip and with such a large outfit. A large raft was constructed from four cartwheels which, being entirely of wood, were light and buoyant. Four buffalo hides sewn together were spread over this framework of wheels, the whole forming an ingenious and trustworthy craft. Upon it the carts and their contents were ferried, the raft being pulled from one side to the other by means of a stout rawhide rope.

We turned our oxen loose upon an island in Sun River; the while the most of the men proceeded to Helena in order to procure material necessary for the construction of the additional carts which would be needed to freight our goods home to Morley. I was left with two of the teamsters to look after the oxen. This island was the home of a very large colony of skunks which I, to pass the time and to impress the others of the party with my prowess as a hunter, proceeded to exterminate. The other members were impressed and said so plainly every time I came near them.

When the party returned from Helena, they brought a number of old cannon wheels upon which they made the mounted cart bodies. With our augmented caravan we then proceeded to Fort Benton. At that time the Fort was a busy bustling place. It stood on the Missouri River which was navigable up to that point. It also formed a base for prospectors going into the Black Hills country in search of gold.

While at Benton we heard of the Custer massacre and in consequence when about to start for Morley we were all armed, my particular weapon of defence being an old rimfire thing, which was liable to be as deadly at one end as at the other. However, our fears were groundless, as we saw no hostile tribesmen on our long journey back to the Valley of the Bow.

An experience that stays fresh in my memory had the Sweetgrass Hills for a setting. There, one morning at dawn, I rubbed my eyes awake and went out with one other man to round up the oxen. On locating the animals we were surprised to discover an old bull bison quietly grazing amongst the oxen. I ran breathlessly back to camp and got an Indian [sic] of our party to come and shoot the great shaggy beast. One of our cartwheels had broken down and so the hide of this bison was made use of at once in repairing the damage. This was accomplished by sewing part of the green hide over the fracture and when it had shrunk and dried it made the wheel as serviceable as ever again. We took the best of the buffalo meat but the weather being hot and sultry, it soon spoiled and we were obliged to throw it away.

One night instead of sleeping as usual under a cart I crept in under a cover and found a most comfortable sleeping place amongst some sacks of flour. In fact so snug was I, that it was ten o‘clock next morning when I awoke to discover the whole camp in despair of ever seeing me again. They had been out searching for me all morning, and I sure did get a calling down for delaying the outfit a whole five hours. We usually broke camp at five a.m.

On another occasion, I went to Benton to meet my mother and returning had a disagreeable mishap. I had purchased ten gallons of coal oil, and the jarring of my cart caused the cans to leak so that when I reached Morley the precious oil had entirely disappeared. We had to revert to candles as a means of illumination during that winter. Every time I read of an oil strike in Southern Alberta it reminds me of that incident.

When I. G. Baker established stores at Macleod and later at Calgary, it relieved us of that long trip south to Benton.

In the fall of 1877, I was permitted to accompany the men of Morley on a hunting trip. They proposed to go after a supply of buffalo meat. These animals were becoming somewhat scarce over the plains. After being out scouting for them for a few days, we finally sighted a small group near the Bow River and at a point some distance west of the present town of Gleichen. It was almost dark then so we decided to camp. A half-breed Indian [sic] and I went towards the river‘s edge to cut some poplar for the campfire. As soon as my companion laid the axe to a stout tree there was a most unearthly clatter and a shower of bones came rattling about our ears. Unwittingly, we had desecrated the last resting or roosting place of a long-departed Blackfoot brave.

Some time previous to the coming of the railway to Calgary, I rode a horse in a race against a number of half-breed [sic] jockeys. This race was run on the open prairie almost where Eighth Avenue in Calgary now stands.

During 1882-1883, I freighted goods from Calgary to Kananaskis for the surveyors who were working on the line of the Canadian Pacific through the Rockies. I also hauled and skidded the first saw logs for Col. Walker’s mill in Calgary. In 1885 I was out with Steele’s Scouts in the capacity of a teamster. From 1886 to 1892 I was employed as a foreman on the cattle ranch of George Leeson. At that time he held the Indian [sic] meat contract. For the next seven years, I acted as Indian Agent [sic], spending five of them at Morley with the Stonies, and the remaining two at Gleichen with the Blackfeet. During the construction of the great cement plant at Exshaw, I operated a store in that village. Since then I have been with the Parks Branch of the Dept. of the Interior and at the present time (1923) have

supervision of the Game and Fire Protection staffs in all Western Parks.

Banff, Canada. Jan. 1923

Howard married Rettie Grier, daughter of William Grier, one of the first Indian [sic] agents at Morley. Howard and Rettie had seven children, six girls and one boy – Alma, Mary, Dell, Georgina, Hugh, Kina, and a seventh little girl who died very young. Hugh, Mary, Georgina and Kina moved to Los Angeles. Dell married James I. Brewster of Banff, and Alma married G. E. Hunter, also of Banff.

In 1923 Howard was appointed Superintendent of the Kootenay National Park, a position he held until his retirement in 1928. After retiring, Howard spent his summers in Banff and his winters in California.

Rettie Sibbald died in 1938, and Howard died two months later in Banff at 73 years of age.