by Mrs Leslie Towers Big Hill Country pg 786

Francis Towers, born in 1848 in Birmingham, England, left home at the age of 18 years. Having heard so much of Canada, he decided he would manage to get there some way. The captain of a cattle boat took him on as a helper and he worked his way across to Canada. Upon his arrival, he found work on a dairy farm at Kingston, Ontario, where they milked 120 cows. Four men were employed for the job. Needless to say, there were very seldom four, as it was a continuous job, milking by hand. He stayed there for two years. Hearing of work on the C.P.R., he left the dairy and headed for Toronto.

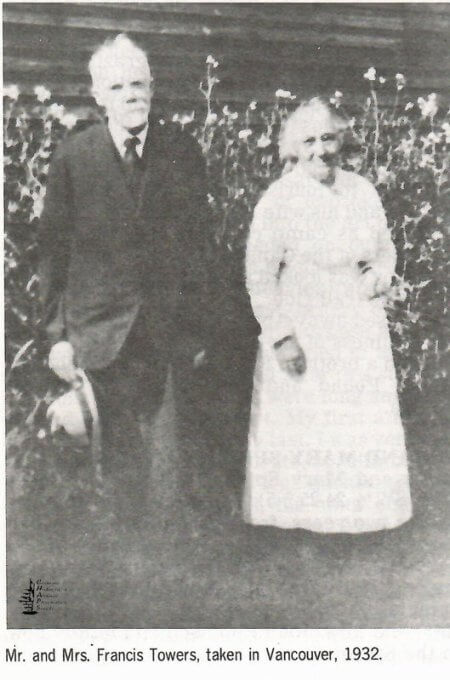

Upon reaching Toronto, Frank, as he was called, met and married Elizabeth Glover, who had come to Canada from the Guernsey Islands, just off the coast of France. The doctors had only given her six months to live, but she was determined to come to Canada and lived to a ripe old age of 88 years. Her first child died of tuberculosis.

Frank continued working for the C.P.R. and was promoted to foreman. He was given the job of laying rails to Calgary from Winnipeg, which at that time was the end of the line. He had 40 men working for him. Anxious about his job, as jobs were hard to get, he had been working westward two weeks, when he suddenly remembered that he had left his bride in the immigration shed in Winnipeg. He rushed back to

find she had searched the town, going from door to door asking for work. Luckily a Mrs. Miller, who had a large family, took her in to sew for them and kept her until Frank came back. From Calgary, the family went back to Winnipeg. Wanting to get to Vancouver, there being no passage through the mountains at that time, he and his family travelled via San Francisco and on to Vancouver where he worked on the Waterfront Hotel until it was completed. He then went back to the C.P.R., which at that time had reached Mission, British Columbia. Their son Walter was born at Yale, British Columbia, in 1879.

At that time the C.P.R. had brought over 1000 Chinese to work on the track. One day someone hollered “Fire!” Every worker dropped his tools and headed for Vancouver. They had to come back or be deported. At Yale, the mosquitoes were so bad that despite lining their tents with netting and paper, the family found it impossible to put up with them, so left the C.P.R. again and journeyed back to Alberta where he rejoined the company. Frank was promoted to foreman and stationed at Cheadle at the time of the Riel Rebellion.

Elizabeth Towers and her children, along with the telegraph operator, were alone when word came that the Indians planned to attack Calgary that night. The operator immediately crawled up into the attic. Fortunately, Frank arrived back and waylaid two Indian [sic] scouts. He locked them up for the night and by getting word to the Police, he was able to stop the Indian [sic] attack.

Many were the stories they told of their experiences with the Indians [sic] stealing cows and chickens. Mrs. Towers had many close calls. An Indian [sic] appeared at the door one day and asked her if her man was at home. She said he was. The Indian [sic] didn’t believe her, after knowing he was up the track. She kept backing up to the stairway, the Indian [sic] following. Suddenly there was the sound of boots scuffing over the upstairs floor. The boys had been asleep and on wakening had slipped into their dad’s big boots. The Indian [sic] tore off as if shot!

Leslie was born in a log house at the junction of the Bow and Elbow rivers at Calgary in 1884. At that time Calgary was mostly tents. Leaving Calgary, Frank began to accumulate some cattle and by the time the C.P.R. reached Mitford, he had approximately 90 head. The railway inspector came along one day and told him he could not hold two jobs and advised him to take up land and look after his cattle.

Frank and Elizabeth finally settled on their homestead on the NW14 20-25-4-5. By this time, seven children had been born to them. Three died in early childhood, leaving Walter, Leslie, Harold and Vera. The Towers built their log house near the Jumping Pound Creek. William Edge and Charlie Pedeprat dovetailed the logs and helped complete the house, which was comfortable and quite spacious for the time. The

Copithornes were their closest neighbours, and the families were always ready to help one another. They shared the beef whenever butchering time came around and helped each other in various ways. The Copithornes had come to the district and settled two years after Frank and Elizabeth. It was a friendship that lasted all their lives.

The time came for the children to go to school and Leslie and Harold stayed with the John Copithornes so that there would be enough pupils to open a school at Jumping Pound. Later the three boys rode to Mitford to school where Miss Monilaws taught. They also boarded at the James Quigleys where, according to reports, there was more mischief than learning. One Hallowe’en the young fellows locked all the Chinese in Cochrane in the outhouses and loaded them onto a boxcar. They landed in Calgary the next morning.

Mr. and Mrs. Towers drove by wagon to Calgary for a six months supply of groceries in the spring and fall, always stopping at the Bob Wallaces or the Frayns in Springbank. Mrs. Towers said when they first settled she was two years without seeing a white woman. She made all her soap and candles, all the boys’ overalls, smocks, etc. Like all pioneer women, her life was very hard – bearing most of her children without a doctor and sometimes only an Indian [sic] woman as a midwife. While Frank was working for the C.P.R. she cooked for as many as 50 men, mixing bread every morning in a big round washtub. She was a very small person but had wonderful stamina and was known as a very hospitable, gracious person. She said that often she would come downstairs in the morning and have to step over ten or twelve cowboys sleeping in the dining room, in order to get breakfast for them. As an old lady, she talked of the large herds of cattle scattered over the hillsides where the different ranchers claimed their own, following roundup.

Half a mile down the creek there was a buffalo jump where the Indians [sic], years before, had run the animals down the coulee and over the bank. Many a load of buffalo bones were taken out of there for years after.

Mr. and Mrs. Towers left the ranch in 1914 to live at Kitsilano Beach, Vancouver but would come back to Alberta in the summer. In 1928, Francis Towers divided his ranch between two sons Leslie and Harold. He was a very hard worker and a good friend to everyone. He died in 1936, at the age of 85, pushing a wheelbarrow of wood for his fireplace on the beach at Kitsilano. After his death, Mrs. Towers lived alternately with her sons and daughter and died in 1939, at the age of 88 years.

Of their children: Walter married Miriam Edge, and they had three children, two girls and one boy. Walter tried various ways of making a living. He went into the butcher shop business with Ernie Andison in Cochrane for a time but his wife’s health was not too good. They went to Vancouver where he worked for British Columbia Electric for 25 years. He died there and Miriam lived in their home for quite some time before moving to a Senior Citizen’s home, where she died.

Vera Towers married a Scotsman, Robert Shaw. They lived at Penhold, Alberta, for four years then moved to Carstairs, where Mr. Towers had bought the Sam Scarlett ranch for his son Walter and his son-in-law Robert. This ranch was the only place between Calgary and Edmonton where travellers were sure of getting water for their stock. Mr. Scarlett charged twenty-five cents a pail for the water. Robert and Walter farmed this place for a short while. Walter did not care for ranching and left Robert to continue with the farm. Robert and Vera had three sons, Alex, Frank and George and one daughter, Bessie (Mrs. Ivan Pointen). Vera passed away in November 1963, at the age of 79.

Harold Towers was born in the section house at Radnor. He married Dorothy Fitch in 1915, and they had three daughters: Kathleen, now liv

ing in Winnipeg, Betty in Victoria, and Shirley in Vancouver. Harold sold his part of the ranch about 1946 and moved to Calgary, where he bought two large apartment houses, with which he has been very successful. He is now 83 years old and a very prominent member of the Calgary Gun Club, winning a prize for the best shot at 83.

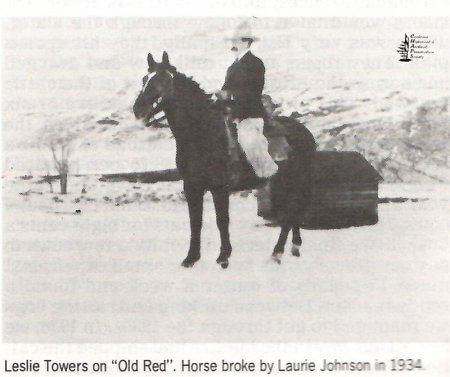

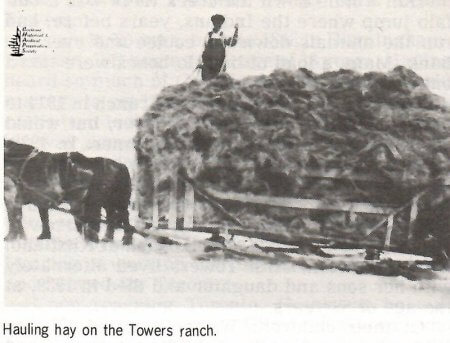

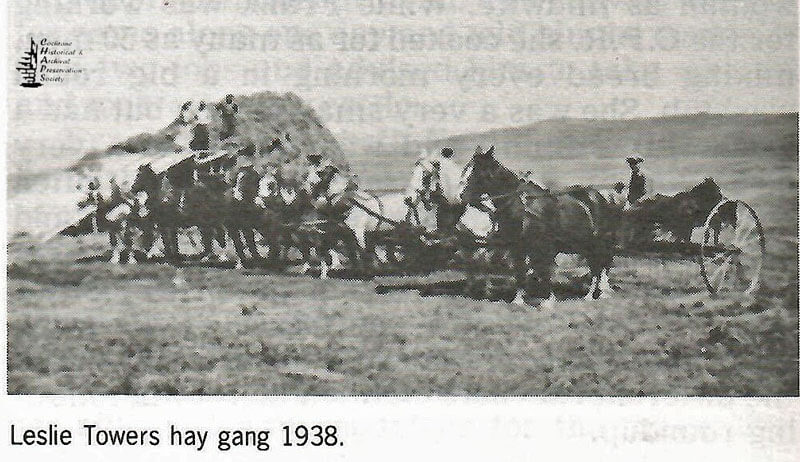

Leslie Towers homesteaded SE 14 28-25-4-5 and continued ranching, which he loved. He was known for the quality of his cattle. At one time, he and Harold kept 60 head of horses but as the cattle increased, most of the horses went.

In 1917, Leslie married Edith Callaway, and they had one daughter Alice Vernice.

Ranching was never too profitable a way to make a living. Every fall when the steers were sold, the bills were all paid and in the spring we were back to the bank again for money to buy bulls. If there was any profit, it went back into buildings and fences. In April 1938, Mr. Coppock of the Merino Ranch and Leslie decided to ship ten carloads of cattle to Chicago, the price was so low here. The cattle were trailed to Cochrane Stockyards by way of the old steel bridge, by Rattrays. At times they had great difficulty crossing the bridge and the cattle would break through the fences, into the swift Bow River. The riders would have to follow through the water, which was very risky. Finally, they hit upon a plan. They roped an old milk cow and dragged her across the bridge, and the rest of the cattle followed. This procedure would take five or six hours and the buyers would still insist on the three percent shrinkage. One carload of Leslie’s cattle topped the market at $8.75 per hundredweight in Chicago. We sold fat cows that same year at 114 cents per pound, $15.00 for 1200 pound cows. Harold Callaway sold oats for eight cents a bushel. We finally decided to milk a few cows to pay our grocery bills and other small expenses. I made 75 pounds of butter a week and found a ready market. Between milking and raising hogs we managed to get through the 1930s. In 1936, we lost all our hay in the big fire and shipped the cattle to Olds, to winter at huge straw stacks.

During this time the government was paying men $5.00 per month to work on the farms and ranches and paid the employer $5.00 for board and room. Looking back and comparing circumstances today, the comparison is hard to realize, if one had not been through it. We all had to work very hard but took it for granted. It was the life we had chosen and there never seemed to be the resentment that came with the more affluent times. I feel the Depression was a good lesson for all who went through it. We were never hungry, depending on our gardens, milk and eggs. Our pleasures were simple, skating, playing cards and games around the kitchen table by the coal oil lamp in winter.

There were also special occasions: The Fireman’s Ball, Ladies’ Ball, Bachelor’s Ball, and many others. Everyone went dressed for the occasion, in lovely evening gowns, belonging to the better-off folk, or the shorter dresses, to the ankle, never above! Two bachelor brothers never came without their white gloves – a protection for the ladies’ dresses. There were popular card parties at the different homes during the winter. We rode horseback or drove by buggy. There were picnics in the summer. The mothers were never too busy to bake all the day before, loading everyone into the democrat and driving five to six miles and getting back in time to do three hours’ chores in the evening. On cold nights in the winter, we would put hot bricks, for warmth, in the bottom of the sleigh and drive to the neighbours or to the dances. It was a wonderful thing when the little heaters with charcoal were invented.

Our daughter Vernice married Hugh Wearmouth, son of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Wearmouth of the Glendale district. Leslie took Hugh into partnership with him and after Leslie’s death, September 16, 1963, Hugh managed the ranch. Hugh and Vernice had four children; the first boy died at birth. A second son Douglas is now with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police after spending two years on the City of Calgary Police Force. Irene graduated as a Registered Nurse from the Holy Cross Hospital in Calgary and is presently working at the Calgary General Hospital. Edith trained as a Certified Nursing

Aide in Calgary and is working for the City of Calgary Health Department. On August 18, 1973, she married Lindsay Ecklund, a Saskatchewan boy, who is working with Hugh on the ranch.

They reside in Cochrane.

I still live in the house we built in 1917 on our ranch, NW14 20-25-4-5. This is the quarter that Francis and Elizabeth Towers homesteaded so long ago. Their original log home is still standing directly across the Jumping Pound Creek from my home.

The Towers brand is the original brand of Francis Towers, the “Wineglass’ on the left shoulder for horses and on the right hip for cattle. Hugh Wearmouth’s cattle brand is Double S Bar on the right rib.

Great story…thanks for sharing! Impressed by individuals simple desire to work. Seems people were just more courageous then and willing to do whatever it took to provide for their families. Wish some young people today would show the same courage, sad that we can’t get people to take jobs, particularly in the agricultural sector, that would sit vacant without importing foreign labour.

These stories offer valuable lessons, thanks for sharing.

Thank you very much for this lovely story. I think it would be wise to add a note, a footnote of some kind, saying that perhaps some stories of the “Indians” were a little bit exaggerated in keeping with the understandings of those times, or that the names of the First Nations of that region, and so of these people, were “xxx” as to what research you have that would know of who these people were. I haven’t met a First Nations or Metis person who would ever have countenanced the kinds of behaviour that are imagined here, or have Elders and grandparents that would have taught such menacing kinds of behaviour, so I’m not sure that these stories could really be true, or maybe it’s more that people of those times, and us today, had certain stereotypes that we should all try to correct. Also to call a kind of people “Chinese”, like Chinamen, could be a bit doubtful. Those are people we’re talking about; in my family we have Chinese people, and they are people they are not all just the Chinese that got locked in the outhouses, those are some real people that suffered just or much ore more than the pioneers that are being discussed here. It seems good that the story puts in “sic” after Indian, but maybe at the end there could be a note about why that is done. Our family, we are many cousins, about 80, some in the Cochrane area, are all quite well off, happy in this country, because of the land that the Government “gave” us to homestead, but sometimes that land hadn’t ever even been given up by the First Nations, and some of them have still got nothing for their land. And so I think that a lot of us could be thankful for where we’re at in this world, and say a word of thanks and understanding about that.

There is talk of creating an Indigenous Centre in Cochrane. I hope that goes forward so we can better tell that story. If you’ve not seen the link it’s on our CHAPS and Cochrane Historical Museum Facebook pages just this morning.

I’ve never met a person who would condone the wholesale slaughter of bison. Does that mean the stories of the huge bison hunts aren’t true?

Discarding a story because you “haven’t met a First Nations or Metis person who would ever have countenanced the kinds of behaviour that are imagined here, or have Elders and grandparents that would have taught such menacing kinds of behaviour” really doesn’t mean anything.

Tom, it’s good that civilised people can have a calm discussion like this. I enjoy reading the original story by Mark, and what you have written and thinking about it, and I will get back to this. At the moment: work, preparations for holidays, etc.

I hope you are all starting a nice Christmas season of your own!

p.s. Wonderful that Cochrane would work with First Nations, Metis, on creating an Indigenous centre. Sounds like a massive undertaking, lots of respect due for even entertaining the idea.

(Also, sorry if this comment appears twice – seems like I might have done something wrong witht the post.)

Tom, about the bison, it is true it is not praiseworthy that there was the wholesale slaughter, by the white European immigrants to North America, when for some 30000 years the first peoples of this continent had been able to live in balance with those animals, and with all of all the other species at home here with us.

But each year we still slaughter about 40 million cattle in the USA and Canada, and you have something there, this is something to think about, because know that the production of cattle as food has a greater impact on our global environment than any of our other foods. Still, myself I like a good beefsteak every now and then, and other meat regularly, so I’d be the pot calling the kettle black if I objected to indigenous people having killed bison in the long ago.

We could possibly go further by discussing people, not only bison and cattle, which was where the conversation started.

I think we are proud to be Englishmen, when we write the stories of our ancestors, and still today, descended from Englishmen and others as we have become mixed. We would be offended if we were called by some other term, such as “slimy limey”, which is the kind of offence that some Indigenous people say they feel from the label “Indians”. Even if it were not an insult, we would not like it, we would not write it, that our ancestors were just White, or Europeans, when we are proud to have been English, German, French, Italian, Czech, Icelandic, Russian, and all of the other 45++ nations of Europe. And so I think we could understand why Indigenous peoples of Alberta would also like to be recognised by their own names that they give to their Nations.

Whenever I think of these issues I cannot also help thinking of how rich I am, among the luckiest of this whole world, here in Canada … me, my brothers and sisters, all my many cousins, about 80, very few, almost none who have fallen on hard times in their lives – illness, early death, mental illness, addictions – these things have happened, but only to few, and then we helped each other, the rest of us were okay, had a basis, had a start, and so we’ve helped pull the suffering out of their problems, and none of us have died except for reasons of physical health and old age. And all of this, if we had not left from our home Nations in Europe, and been assigned lands by the Canadian government, would not have been possible. I have been to Europe, and I have seen the difficulties we would have had if our ancestors had stayed behind there. And those lands that we received, that gave us our start, came from the Indigenous people, and many of them did not agree to give them up, or only under severe need of an already difficult situation for them. And some of them, instead, many of them, have died, have been beaten, starved, punished, sexually abused, died as small children, and still worse, their families have been so damaged that for some it is difficult to find the help, to give each other the help they need, of the kind that has saved the ones of my families, who had trouble. And so I feel that at least one thing I can do is to try to understand who these people are, and include to try to call them by their names, recognising they say that is what they want. It seems a small thing in return.

Thank you so much for listening, for reading, and my great respect to the Cochrane Museum, to you Tom, to your ancestors, to Mark and his ancestors, to all those who have come before us, and taught us how to live together in this world, and whose honour we try to uphold.

Thank you.