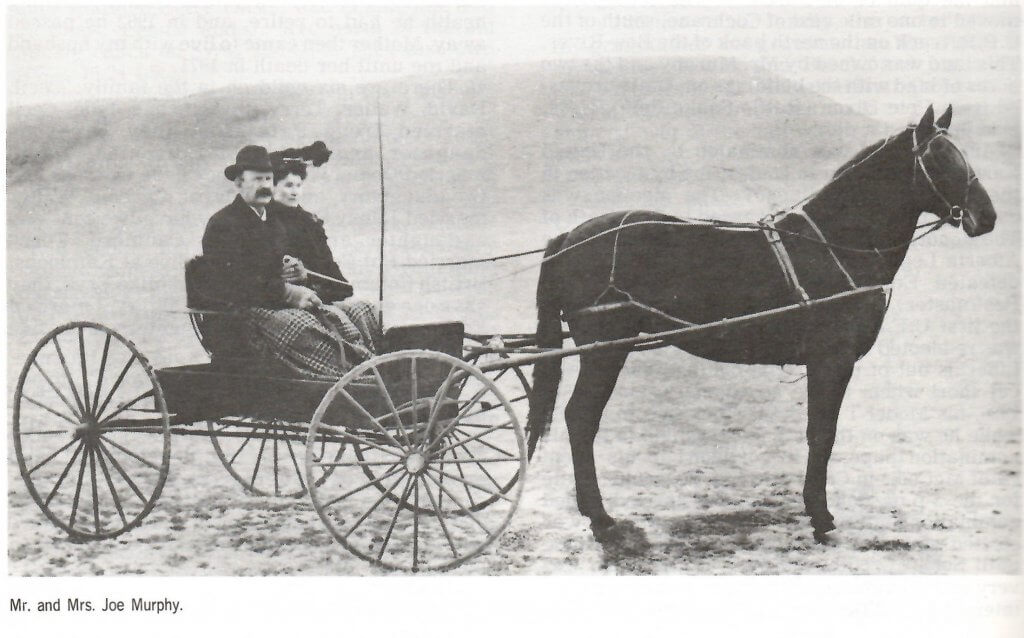

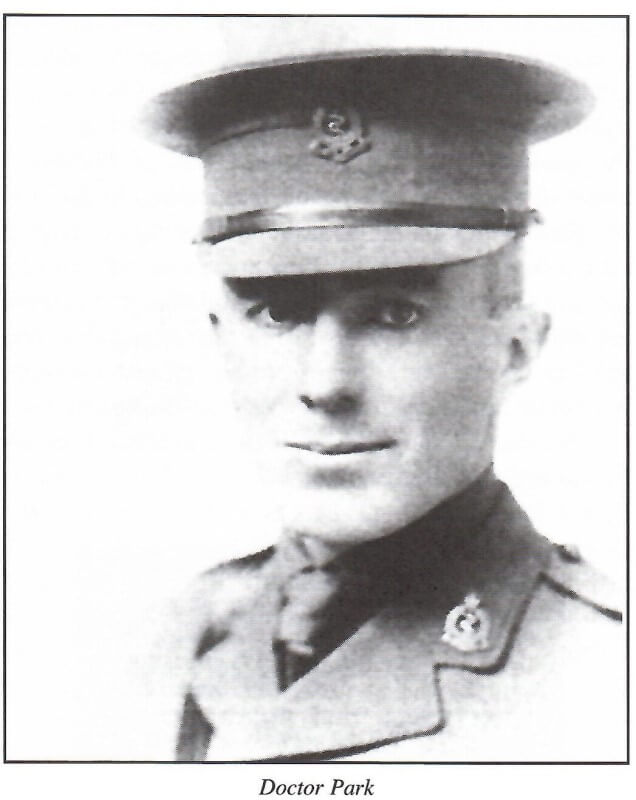

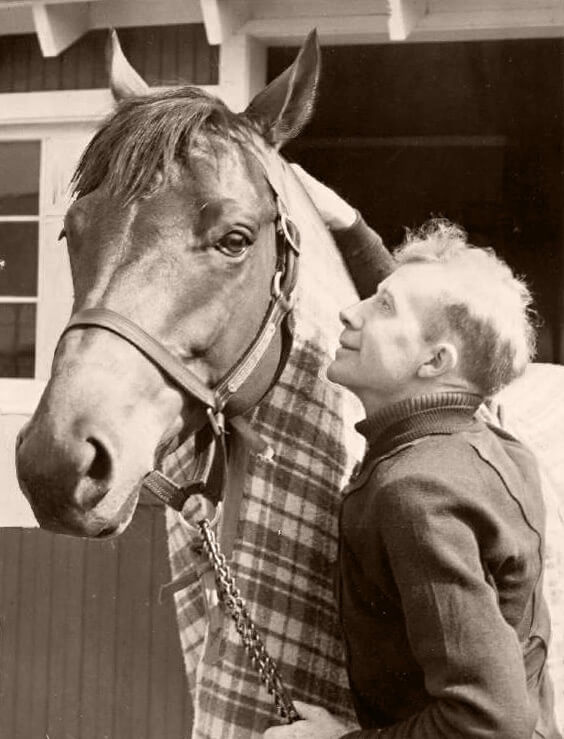

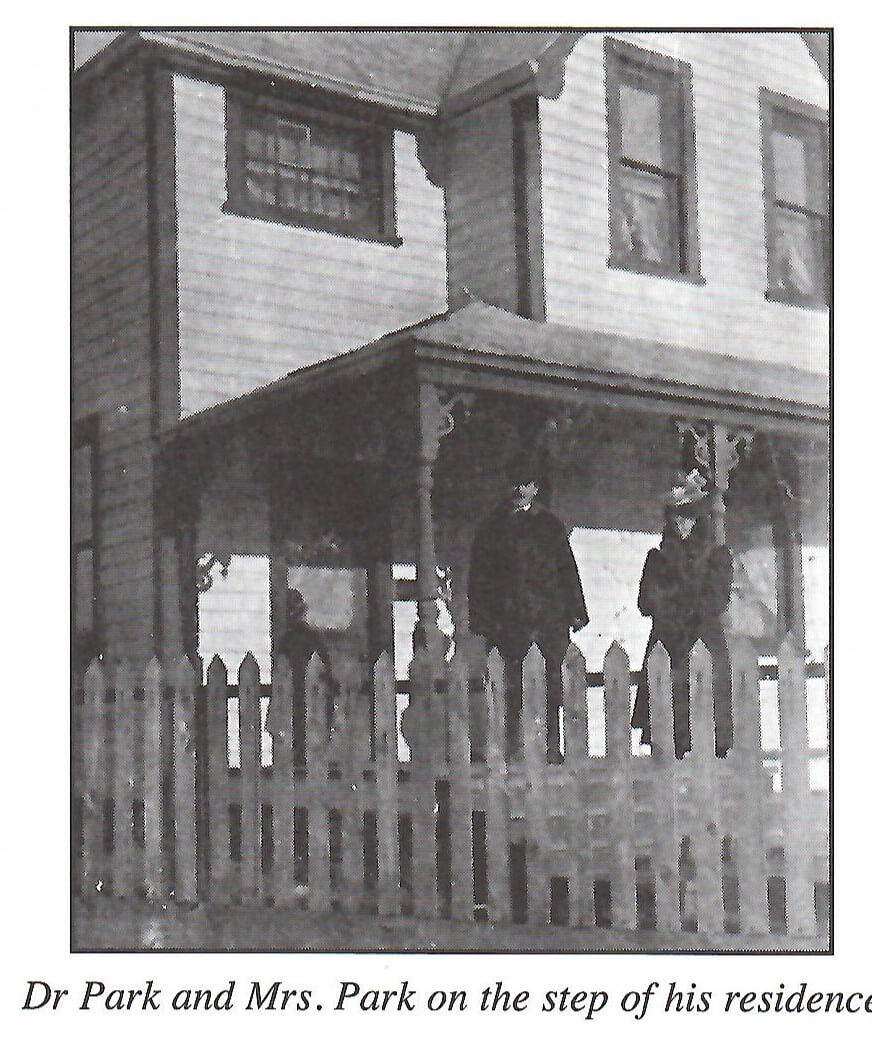

In those days, most patients were treated in their homes and the doctor made his rounds from home to home as often as necessary carrying his surgical instruments and medications with him, If they were so sick they couldn’t look after themselves, there was usually some neighbour who could help. In 1906, he married a teacher from his hometown in Ontario and they set up housekeeping in Cochrane. At this time he bought a horse and buggy to do his rounds. He later bought one of the first cars in Cochrane. In 1915 Dr. Park left Cochrane to serve in the armed forces during World War 1.

A few stories told by his patient’s highlight problems faced in that era.

Hank Bradley; in 1913 at the age of six years had one of his fingers chopped off by a man cutting a soup bone off a shank of frozen beef with an axe. The boy was holding the beef so it wouldn’t slip at the time. The man who wielded the axe soaked the wound in saltwater and wrapped it in a towel while he went and caught and harnessed a team of horses. Then he had to go to a neighbour to borrow a democrat before he could take the boy to the doctor. The doctor had to tie him down to work on his finger.

John and Lucy Morgan homesteaded in the Bottrel area. Lucy went into labour on November 24, 1908, during an early winter blizzard and a temp of -20F. They sent their 13-year-old son by horse and sleigh to fetch Mrs. Dawson, the midwife, who lived seven miles away. She gathered up her equipment and back they went through the cold and driving snow. It was a complicated labour so Dr. Park was called from Cochrane. He hitched up his horse and cutter and arrived sometime later. Luckily the brave mother was finally presented with a healthy baby. Because Lucy was confined to bed for a day or two, Mrs. Pogue came and stayed with her until she was well enough to look after her family. The next year, Mrs. Pogue had a baby at home so she sent her two children over for Lucy to look after while she too recovered from her labour. A Neighbour helping neighbour allowed people to survive.

Lou Shands was hauling firewood in the bush in 1905 when his team ran away. He was thrown off and broke his leg badly. He was hauled to his home on a stone boat and someone rode into town to get Dr. Park. By the time the doctor arrived many hours after the injury, the leg was so swollen that after it was set the cast would not hold it properly. He was eventually left with a marked limp. In 1945, Lou took seriously ill on his farm right after a blizzard had closed all the roads. This time a more modern ambulance, an airplane, took him to hospital in Calgary. Such a change in one man’s lifetime.

Edith McKinnell and her husband John homesteaded in the Bottrel area after arriving from Scotland. Edith had been brought up in a rich family with servants to do all the work. It was quite a culture shock to come to an area where only the very basics of life were to be had and where she spent months without seeing another woman. All five of her children were born in her home without medical help with only her husband to assist. Sadly, the first baby died at birth but luckily the rest survived and thrived.

Elizabeth Winchell and her husband Frank homesteaded near Water Valley. Two of her babies died at birth at home but one son survived.

Dr. Thomas Ritchie

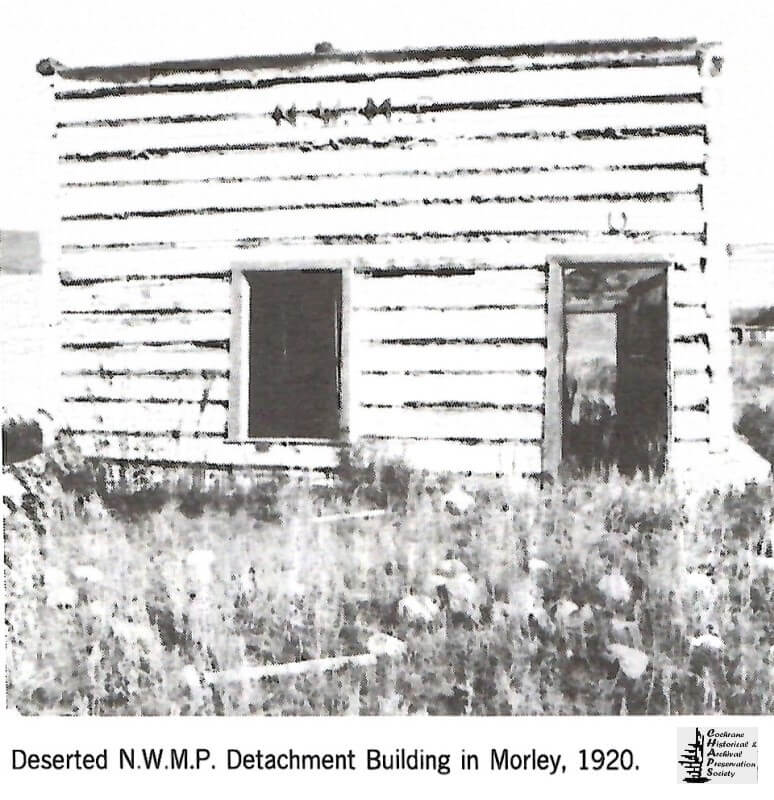

Dr. Ritchie arrived in the Cochrane district in 1904 with a wife and family of eight children. He had been practicing for a long time in Virginia USA and it appeared he had done well financially and moved here to invest and farm rather than continue doctoring. He bought a small ranch near Mitford that is now part of the Morley reserve. He also purchased land at the mouth of Jumping Pound Creek. There he ripened and sold the first wheat ever shipped from west of Calgary. Of course, he couldn’t refuse to treat people if they needed help when Dr. Park was away. In the fall of 1919, his car overturned in the ditch during a snowstorm and he died from his injuries three days later.

Some stories survive that involve this doctor.

Dave Bryant was six years old when he fell off a horse and broke his arm. He was taken to Cochrane but the doctor was away so they took him to Dr. Ritchie’s ranch. There the doctor with the help of his son was able to set the bones. No anesthetic was used. Alcohol, morphine and cocaine were about the only means of relieving pain that doctors had in those days. A child of six could be held down by a strong man while the bones were reduced. This seems cruel but it had to be done so there was no alternative in this case.

William Tempany froze both feet hauling hay in the winter of 1906. Dr. Ritchie was sent for and came from his home on the ranch to do what he could for him. Part of one foot had to be amputated later.

Anne Steel was knocked down by a horse and broke her leg. Dr. Ritchie came to their farm by horse and buggy to set it. For a cast, they wound strips of bedsheets soaked in hot starch solution around the leg. As it cooled and dried, it hardened enough to do the job.

Communicable Diseases spread unchecked because of the lack of immunization and few medications that were effective.

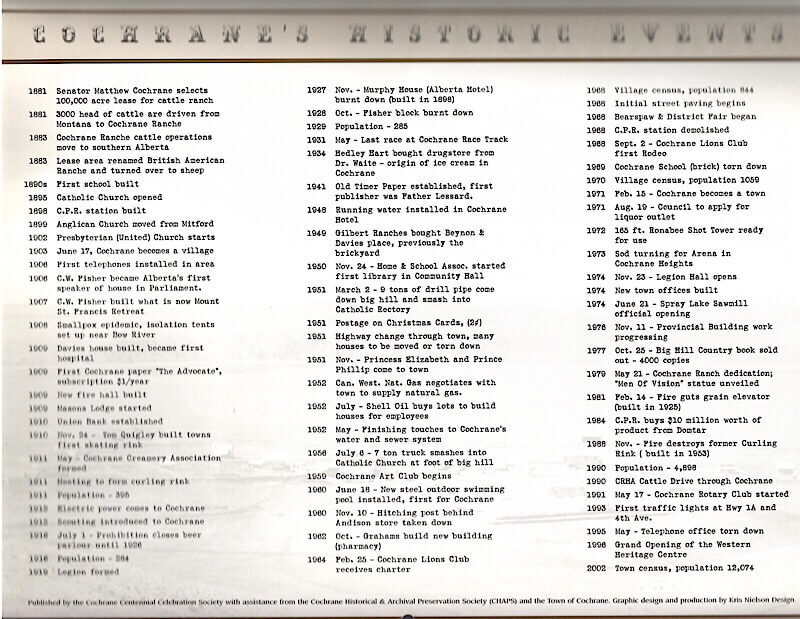

Smallpox still occurred although vaccination had been available for many years. In 1908, an epidemic occurred in Cochrane. Tents were erected down by the river and anyone with smallpox was sent there. Guards were stationed on the roads and at the railway station to prevent anyone from entering or leaving the town for any reason. These guards carried rifles and enforced the quarantine to the letter. Rev. Sale, the priest at All Saints Anglican Church at that time, rode into town on horseback to visit a parishioner without knowing about the quarantine. When he was challenged, he ignored the order to stop. He stopped in a hurry when a shot was fired over his head. When no more cases occurred, every resident had to take a bath in an approved disinfectant before the town was declared safe and the school could reopen.

Scarlet Fever was a serious disease in those days before penicillin. Many adults and children died from its effects and many developed rheumatic fever, kidney problems and chronic ear infections as complications from the disease if they survived. In 1910, it was prevalent in the district. Jack Dowson and his niece Lily Johnson died from it.

Diphtheria took the lives of many children. They would suffocate because a membrane would sometimes form over the breathing passages, or the toxins from the disease would affect the heart, kidneys or nerves. In 1898, the Scotty Craig family was infected and the oldest son died at age 10. Andrew and Suzanna Nagy lost two of their oldest children to the disease in 1915. In 1924, Elizabeth Phillips (nee Skinner) in the Lochend area, died from diphtheria leaving her husband with three young children to raise. It was not until the 1930’s that a vaccine was available although an antitoxin was available prior to that. Antibiotics, of course, were not discovered until the 1940s.

Typhoid fever was also present in the district because wells could be contaminated by poor hygienic practices and there were always carriers of the disease in those days. In 1882, Elizabeth Sibbald died from typhoid, and in 1907 Thurman and Elizabeth Ault lost a son from the disease. In 1911 John Boothby was treated for typhoid fever in the relatively new Davies-Beynon hospital by Dr. Park. In 1917, two of Mrs. Davies’s granddaughters died of typhoid fever. The disease is now controlled by strict public health measures regarding water supply and sewer systems.

Measles, mumps, chickenpox, whooping cough and rubella went around every few years and in those days every child would catch most of them over the childhood years. It was not until the 1940s that the whooping cough vaccine was used and the 1960s that measles, mumps rubella vaccine was available. Chickenpox vaccine didn’t come along until about 1995. It was rare for one to die from these common diseases but serious complications sometimes occurred.

Child Mortality

One of the saddest parts of pioneer life was the large numbers of infants and children that never reached the teen years. Besides the babies that died at birth, there were many that succumbed to complications of communicable diseases, infections of all kinds, and vomiting and diarrhea possibly due to lack of a safe water supply. Lack of availability of medical and nursing care would be a factor as well.

Mr. and Mrs. Andy Clarke opened a butcher shop in Cochrane in 1914. Out of their nine children, two died in infancy. No diagnosis is given.

James Hewitt Family homesteaded near Cochrane and later ran a pool hall and barbershop in the town. Out of their family of thirteen, three died in infancy.

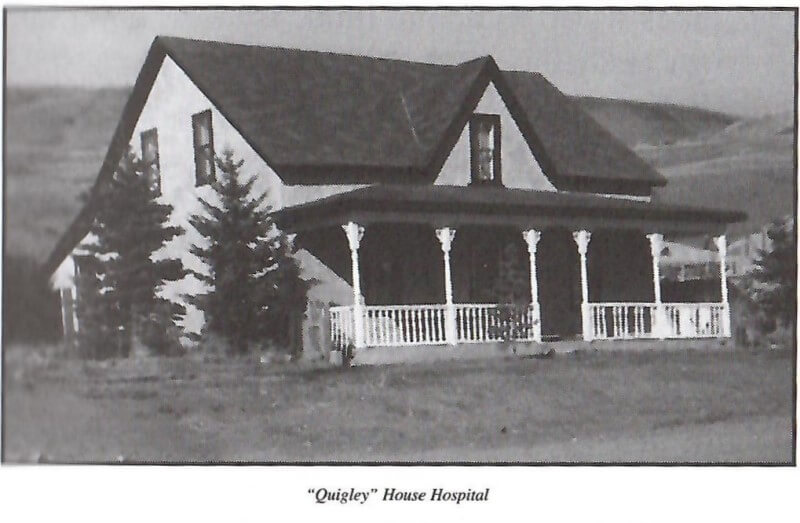

James Quigley Family raised a family on land in the east part of present-day Cochrane. Out of nine children, two died in infancy.

Since there was no cemetery at that time, the Hewitt and Quigley children were all buried on the Quigley farm. When the new cemetery opened, they were all disinterred and moved there.

Rev. David Reid in 1932 came to the United Church in Cochrane. While living here in the manse, they lost their youngest daughter. As usual, no diagnosis was given.

Bert and Lizzie Sibbald had five children. They lost a daughter at age twelve in 1930.

Samuel and May Spicer lost their first child in 1911 to some unknown disease at the age of eighteen months.

Clem and Peggy Edge lost daughter Margaret at 18 months of age from a “heart seizure”.

Charles Harbidge, out of six children born in the Cochrane area after 1905, one daughter died at age eight and one son at age thirteen.

Mel and Christine Weatherhead had a new son born about 1909. While Christine was upstairs looking after the baby, her two-year-old son downstairs had a convulsion of some sort and died. Christine, being postpartum, became severely depressed and blamed herself for the tragedy.

Earl and Letha Whittle had a family of four children in 1912. Six-year-old Gladys suddenly died of pneumonia that year, and two months later ten-year-old Claude died of a “heart condition”

Robert and Edith Beynon had three children. One died in infancy and another at the age of two. Only one son survived. This was around 1930 in the town of Cochrane

Maternity, Nursing Homes and Hospitals

Mrs. Richard “Dickie” Smith (Amy) Her husband died in 1902 on the ranch which later became known as the Virginia Ranch in the Dogpound area. Amy went back to England with her three children to study to be a midwife as she could see the need in this area. In 1903 she set up a nursing home in Cochrane in a log building set back from the street about where the back of the Grahams Building sits now. Mrs. Smith’s nursing home closed after she remarried in 1905. The house later became the Yee Lee laundry.

Mrs. Jack Boldack Used her house as a maternity home and nursing home for several years in the early 1900s. She was a midwife herself but the doctor would sometimes be called to help.

The Davies Hospital

By 1910 Dr. Park needed space for patients that required hospital care. The Thomas Davies family was building a townhouse in Cochrane and they were persuaded to build it a little larger so part of it could be used for hospital patients. It seemed a good fit since Margaret Davies lived there and could preside over it and her daughter, Annie Beynon, had nursing training and could handle that end of the business. This hospital served Cochrane from 1910 to 1915, when it was closed because Dr. Park had left for war service and Mrs. Davies was in poor health.